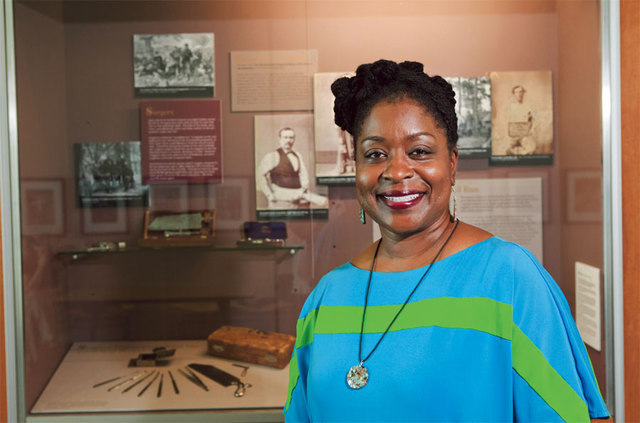

Henrietta Lacks is quietly famous in the medical world. She lived only three decades, but her genetic material was harvested—without her knowledge or permission—to create generations of cells passed around among researchers. Lacks’ line is the oldest and remains the most commonly used for scientific research to this day. At first misdiagnosed with sexually transmitted infections by her local doctor, she actually had the early stages of cervical cancer. Over the course of her treatment at Johns Hopkins Hospital in 1951, doctors took samples of her cervix. A researcher discovered her cells did something no others did: They could remain alive for longer than a few days and continue to grow, providing a host of research opportunities. Lacks died nine months after setting foot in the hospital. She was buried in an unmarked grave. Her descendants, it’s been discovered, continue to struggle financially and don’t have health insurance. Meanwhile, Lacks’ cells have led to countless medical advances worth billions. Cultural Competence Professor Deleso Alford is working to remedy the 60-year legacy of injustice that’s just as tenacious as the so-called HeLa cells. She’s researching legal recourse for Lacks’ impoverished family. For Alford, the case represents one of many in the history of modern medicine. Alford says the present-day health care establishment has an obligation to learn about advances made at the expense of human research subjects—many of them impoverished, their wishes overlooked because of their race, ethnicity, gender, disability or cultural difference. “What her story brought forth to me was issues of patient autonomy,” says Alford, “and the authority of a doctor to look at her and say, You’re 31 years old, you’re a black sharecropper, you’re poor and have five children already." Without being given information on the risk of sterility, Lacks was treated with radium. "The doctor used what he thought was his better judgment to really make the decision for her.”Alford says Lacks’ story raises other burning questions: How do we define legal, informed consent when a doctor and patient don’t have the same cultural understandings about what health means? What if the doctor and patient don’t even speak the same language or don’t understand one another’s accents? She points to parallels between Lacks and present-day medical encounters, such as poor women not being told about alternatives to a hysterectomy. “It’s the same mindset that pervaded in Henrietta Lacks’ time.”Professor Alford, who teaches in Florida, is a visiting scholar at the University of New Mexico medical school through the end of the month. She’s been hosting lectures, discussions and events, some with the African American Health Network and a summer school class on spoken word poetry, which she likes to use as a teaching tool.It might seem unconventional for a health sciences institution to invite a historian, poet and legal scholar to contribute to the curriculum. But UNM’s admission policy spells out its focus. A diverse student body, it says, “is essential for the educational benefits of diversity and for training doctors to practice in New Mexico’s medically underserved communities.” Alford says her time here has given her a better understanding of how academic research can have practical applications, creating doctors who learn from history and practice medicine in more culturally sensitive ways.Medical schools today have to demonstrate that they’re teaching “cultural competence.” In theory, this means that doctors will graduate with enough tools and knowledge to offer sensitive care to patients from a vast array of backgrounds. In practice, Alford contends, cultural competence is complicated and demands a nuanced study of the past. “We’re working on dealing with this issue as a reality, and there is still distrust in many populations for the medical system,” she says. “My research is asking, If there’s a level of distrust present, what do you do about it? Can you teach people to empathize? And how do you teach humility?” The Whole Story Bringing to the forefront those figures formerly confined to the margins of medical history might help, says Alford. In addition to Henrietta Lacks, Alford hopes during her time here to shed light on the story of Dr. J. Marion Sims, considered the father of American gynecology. Sims, broadly painted as a pioneer, operated without anesthesia on enslaved women to perfect techniques and design instruments, such as the speculum. Alford’s also examining the U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee. For decades, unsuspecting African-American men were infected with syphilis by researchers who then left their subjects untreated. Alford says there’s a crucial missing piece of that narrative: The infected men had girlfriends and wives. Many women—and their children born with congenital defects—were also devastated by the government study. Knowing this fuller story can help change conversations about health policy at all levels, from the research lab to the ER.“It brings forward the importance of being patient-centered, knowing that one person is connected to an entire community,” says Alford. “That has to be both taught and learned. How then do you develop a checklist to determine what it really means for someone to submit their health to you? You have to be fully conscious of your roles and responsibilities.”Alford further hopes that expanding health practitioners’ vision of equity and inclusion in the way they deliver care will eventually translate into better public policy. A 2010 report card published by the state’s Department of Health documented gaping, persistent disparities in health care, especially when communities of color are compared with white populations.The time feels ripe for changes, says Alford, in a climate where debates about health care reform are raging louder every day. Sensitive practitioners “have to be in the room,” she says, when it comes to policy discussions.“There’s a definite need for collaboration, and we have to do something so that we’re not just talking about diversity awareness and cultural competency," she says. "We have to really substantiate those thoughts with pointed historical moments and say that we’re not going to repeat history again.”

Deleso AlfordThursday, July 12, 6 p.m.A talk on female victims of the Tuskegee Syphilis StudyAnthropology Room 163, UNM Main CampusThursday, July 19, 6 p.m. A talk on Henrietta LacksDomenici Auditorium, UNM North CampusFor more, go to: bit.ly/DelesoAlford or call 272-2728.