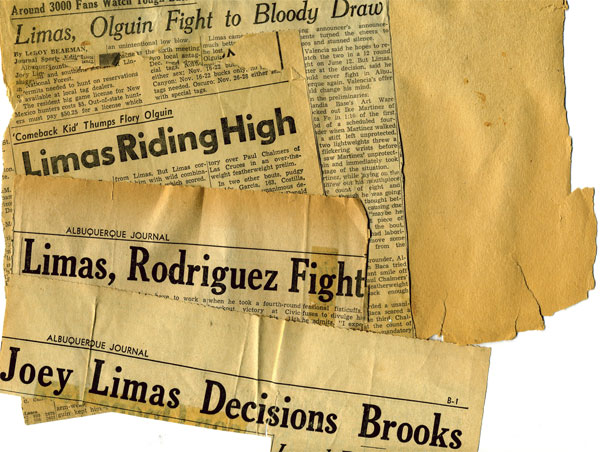

In Memoriam: The Last Days Of Joey Limas

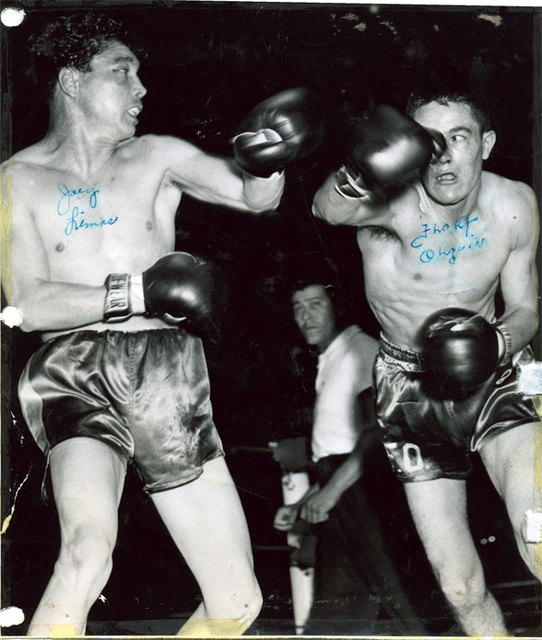

Limas (left) and Flory Olguin circa 1958. The Albuquerque rivals fought six times.

Courtesy of Flory Olguin

Toby Smith

Barbara Garcia and Limas in 1995

Courtesy of Barbara Garcia