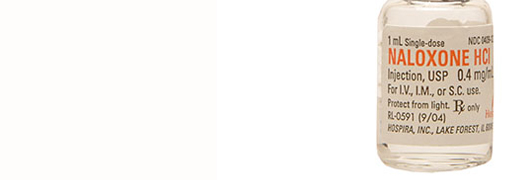

It’s been more than a month since Oscar-winning actor Philip Seymour Hoffman died in his Greenwich Village apartment with a needle in his arm. Despite the nationwide media onslaught of soul-searching and hand-wringing that followed—including a lot of loose talk about a “new heroin epidemic”—in the end, the national and local debate has not been elevated. Albuquerque Health Care for the Homeless Outreach Coordinator Martin Walker said not much new or helpful debate resulted from this intense media focus. “Whenever someone [famous] dies, someone in the public eye, everyone wants to talk about it: the good, the bad, the ugly,” Walker said. “But what they don’t want to talk about is how to fix the problem.” For several years New Mexico has hovered near the top of the list when ranking fatal drug overdoses. To address these dismal figures, activists and health care workers successfully lobbied for laws that treat addiction as a public health issue instead of a criminal justice problem. During weeks of wall-to-wall media scrutiny following Hoffman’s death and years of “Breaking Bad”-fueled methamphetamine debates, this key point has somehow been overlooked. Most medical professionals now view drug addiction as a medical and behavioral problem rather than an ethical or law enforcement problem. This relatively new attitude is reflected in “harm reduction,” a catchphrase trending in the field. Tools that reduce harm to users include needle exchanges, HIV testing, expanded Good Samaritan laws and perhaps most promising, the increasing availability and use of the so-called “wonder drug” Narcan aka naloxone. All these harm reduction tools have both proponents and critics. Only a handful of states permit access to free, anonymous exchange of dirty syringes for clean ones at clinics and hospitals. Confidential HIV testing of addicts is seen by some as aiding and abetting drug use. There has also been resistance to revised Good Samaritan laws that allow companions of overdose victims to call 911 without fear of prosecution. Here’s where New Mexico was ahead of the drug policy curve, being the first state to revisit and amend laws to offer immunity from prosecution for companions of overdosing heroin users back in 2007. New Mexico is also one of a handful of states that has expanded the distribution of Narcan, which Walker describes as the ultimate opioid antagonist. “It’s as innocuous as baby aspirin,” Walker said. “All it does is go into your body and attaches to the receptors in your brain and brushes the opioids off the receptor and covers it [the receptor] like a fist.”Narcan is considered 100 percent effective in preventing deaths from heroin overdose. For that reason harm reduction activists unsuccessfully lobbied for the passage of SB 241. If SB 241 hadn’t stalled in committee, it would have added $600,000 to the Department of Health budget for overdose prevention services. This means HCH could have added 300 additional clients to its Narcan disbursement program, bringing the total number of program participants to 600. HCH has a specialist who helps the organization’s clients find substance abuse treatment. But finding low-cost treatment is difficult, mainly because there isn’t much available. “The big issue is that there is just really not a whole lot there,” said Walker. Many available inpatient facilities want clients to be past the detox stage before being admitted. That’s something that isn’t feasible for many of the nonprofit’s clients, said Walker. Besides inpatient facilities, he said Albuquerque has several programs that offer opioid replacement therapies but—costing as much as $10 per day—their prices put them out of reach for many of the program’s clients. Access to treatment isn’t just a problem here in New Mexico. The Office of National Drug Control Policy 2013 report concluded that out of the 21.6 million Americans who needed substance abuse help in 2011, less than 11 percent received treatment. A New Mexico Legislative Finance Committee hearing to review substance abuse trends and treatment solutions in 2012 reported that New Mexico ranks in the bottom quartile for access to substance treatment. The report also acknowledged that of the hundreds of millions of dollars spent on behavioral health, there is no way to isolate substance abuse spending so decision makers can determine if the money is being spent effectively. In addition to obstacles created by too much demand and not enough resources, Walker said addicts face barriers to treatment because of media messages that frame addiction as a criminal justice issue. Most people involved in the drug trade—whether dealers or users—start off as young, poor members of minority groups. Street drugs like heroin and meth have become a part of street culture in every city in America. “I think it is important that we refuse to allow ourselves to be dragged into the conversation about morality or ‘this poor person’ and feeling bad and all that stuff,” Walker said. “It’s not a moral issue; it’s a behavioral issue.” All this is not meant to imply that Seymour Hoffman’s death was not tragic. But the plain truth is that these individual tragedies occur every day in our own community, and most of those stories don’t even make the inside of our local newspapers. Correction: An earlier version of this article, which appeared in print, incorrectly stated that SB 241 passed to the governor’s desk during the 2014 legislative session. Weekly Alibi regrets the error.

For more stories like this, visit nmstreetpress.org .“Corporate Donors Cash in Under the State’s Proposed Budget Agreement”—bit.ly/nmspdonors"Where Are All the Teachers? Shortages Traced Back to NM Colleges"—bit.ly/nmspteach"The View From the Street: 'Angel' Dishes on Sex Work"—bit.ly/nmspsexwork