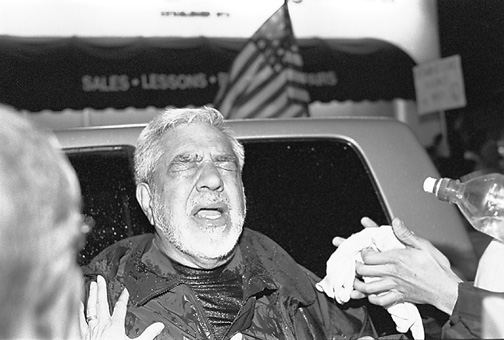

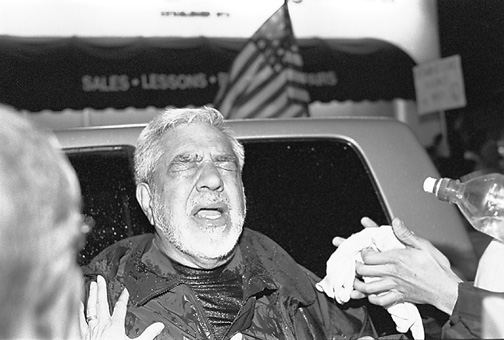

Curtis Trafton had never been to a protest before. He was 50 when the war in Iraq began, and he went with his wife, adult daughter and father to the March 20, 2003 demonstration that began in front of the UNM Bookstore. "I felt that the war was being waged against the wrong people for the wrong reasons," he said. He made a sign out of poster board that said "No War" and found a serious but upbeat crowd when he got to the university. It’s the way the protest went down that propelled Trafton into court seven years later to recall the events of that evening. The demonstration is remembered as one of the most volatile conflicts between civilians and the Albuquerque Police Department. Eleven protesters filed suit against the city and APD officers, saying their civil and constitutional rights were violated that day, including the rights to free speech and assembly. Some are suing for battery and excessive force. "I’m Just Fighting Back" Trafton testified on Friday, Feb. 26, that because of that charged night in 2003, he didn’t attend another demonstration for two years.At first, he said, he stood on the sidewalk and showed his anti-war sign to passing traffic. Then the flow of cars stopped, choked off by police who had blocked the road. So he moved with other protesters into the street and headed east, aiming to again show his sign to traffic. The group swung back west, he said, and he was separated from his family. He hurried forward with his sign over his shoulder, he said, looking for his family and chanting, "Whose streets? Our streets!" with everyone else when he was blindsided by a horse-mounted police officer. The horse’s head struck Trafton in the chest and under his chin, he said, and spun him around. "It was a powerful blow.” He couldn’t recall a chunk of time after that, Trafton testified. He said he heard loud bangs, smelled a strange odor on the air. His wife called him on a cell phone he forgot he was carrying, he said, and the family met up and left the nasty situation."I was furious that a person trying to do a nice, peaceful protest would be put in a situation of danger, to my mind, by police," he said. Two years later, he went to a demonstration on the anniversary of the bombing of Baghdad. He said he was sick of feeling like a coward. "I was raised to fight back," he said. "And that’s what I’m doing here today. I’m just fighting back." His wife, plaintiff Christina Maya Trafton, testified that at the intersection of University and Central, a man carrying a child told her, "They’re going to use gas." Acrid orange smoke billowed in her direction, she said, and her skin and face were burning. "My daughter grabbed me and said, ‘We have to get you out of here.’ ” It was dusk and cold; a light rain was falling. When they got to their car at Silver and Yale, she remembered hearing what she thought were two rifle shots. She called 911, afraid someone had been injured, she said. She called her husband and told him they needed to leave, because she didn’t “want to die in Albuquerque” that night. She initially felt relieved when they left the protest, she testified. "Then I was very angry. I felt very helpless. It left a bad taste in my mouth for APD and police generally."Her husband insisted they attend the two-year anniversary protest. She said she made him drive the perimeter of the site to find the staging area. She wanted to make sure the same force was not present. "We didn’t stay long” at the protest, she testified. "We’d Still Be There Today" Sgt. Steven Hill didn’t get down to the protest until about 6 p.m. on March 20, 2003. He was off-duty, got the call and drove to the location, he said, using his lights and sirens. He’d been told the crowd had broken through the police line and was headed toward the freeway. He dressed out as quickly as he could next to his Suburban, he said, then heard a loud retort. When he looked up, he said he saw a flash and some smoke. Hill testified that he wondered why someone would have chosen to drop a flashbang, a nonlethal stun grenade, in that location—then he realized it was not APD artillery.Part of Hill’s job is to order and catalog ammunition for the SWAT team. He keeps track of who it’s been issued to and when it is deployed. He testified that no officers used flashbangs that evening. But APD did use tear gas. Hill was one of the officers who threw a gas grenade, the effects of which he outlined during the trial. "You could feel like you’re drowning," with your eyes and nose running and tightness in your chest. He said people could feel like they were having respiratory problems.A crowd of students sat in the road, their arms linked, he said. Officers would select one of the sitting protesters at a time and manipulate pressure points on their body to separate them—a common tactic. Some demonstrators sneakily tried to remove others who had been arrested from the hands of police, he testified, and pull them back into the crowd. Officers confiscated backpacks, he said, and two were loaded with clothing and water bottles. One smelled strongly of vinegar, he added. Officers warned the crowd they would use chemical munitions, he said. "It’s important to do your best to get the message to the crowd." The protesters’ drumming and chanting interfered with that warning, he said. "It was quite loud out there." He first tried to use the smallest amount of gas possible, he said. The crowd scattered, he testified, but then came back. Then officers launched four gas grenades to the far side of the crowd. Still, some demonstrators remained sitting in the road. Someone advanced on officers, he testified, with a group in tow. Hill said he ordered officer Michael Fisher to shoot them with pepper ball rounds (pepper spray projectiles).When Hill was deposed in 2005, he said without the tear gas, "We’d still be there today." "Wait It Out" Lou Reiter, a police consultant, took the stand on Monday, March 1, as an expert witness for the plaintiffs to talk about handling protests. The former Los Angeles Police Department officer has been called in other cases to testify on behalf of APD. Over the course of his 20 years with the LAPD, Reiter handled civil rights demonstrations and Vietnam War protests. He spoke of the differences between crowd management and crowd control. In management, police are just a presence. They’ve gathered information and try to anticipate what may go wrong. In crowd control, officers are protecting property and people, and they make arrests. When people are passively resisting arrest—sitting with locked arms, for example—use of force by an officer is not acceptable, he testified. It’s OK to deploy gas and beanbag guns, he said, when there is a high likelihood of injury or damage to public property. In most cases, when chemical agents are used, he said, it’s a good idea to have a means for people to wash the chemicals off, and it’s also reasonable to have medical assistance nearby.After reviewing video tapes and documentation, he testified that at no time did the 2003 march become a riot and the crowd did not fit the definition of a mob. He said without violence and property damage there should be no need to disperse a crowd. "You have to wait it out."

Testimony is ongoing. Check in at alibi.com for updates.