Pour Me A River

Albuquerque Drinks From The Rio Grande

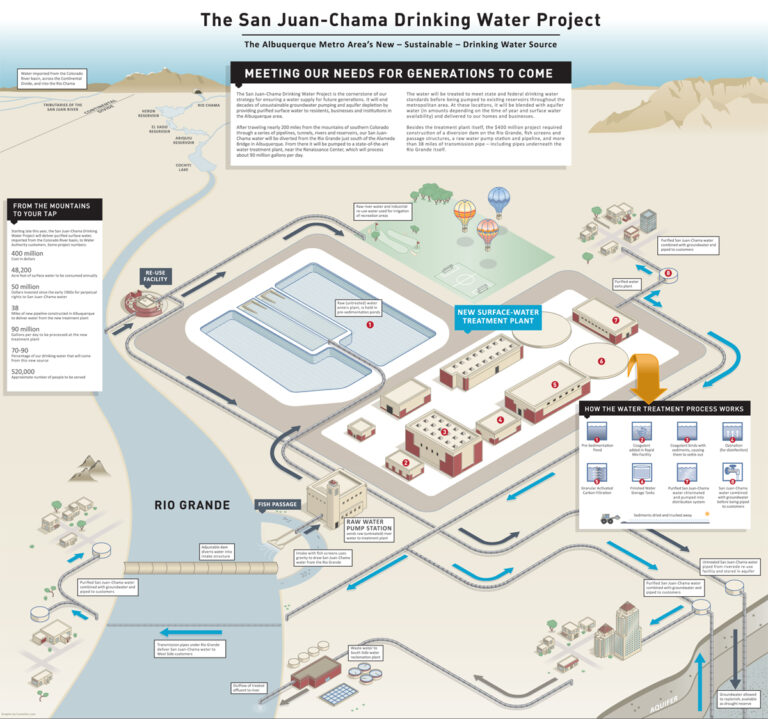

Dozens of miles of pipeline were laid throughout Albuquerque to accommodate the new drinking water system.

Albuquerque Bernalillo County Water Utility Authority