Racing To The Moon For A Terrestrial Super Fuel?

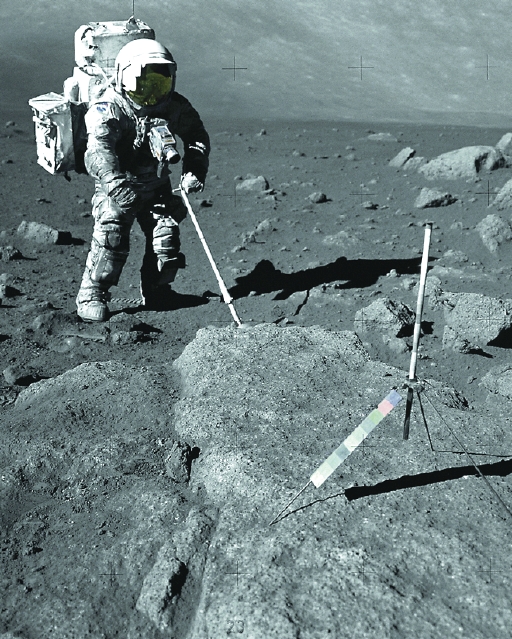

Albuquerque Resident And Apollo Astronaut Harrison “Jack” Schmitt May Have Inspired An International Race To Unlock The Possible Power Of Lunar Helium-3

Theoretically, if lunar helium-3 is ever harnessed here on Earth on a large scale, it could become a major power source.