Study Finds Drugs In The City’s Water

Study Finds Drugs In Albuquerque’s Agua

The Rio Grande, which, according to Amigos Bravos, contains pharmaceuticals.

Eric Williams ericwphoto.com

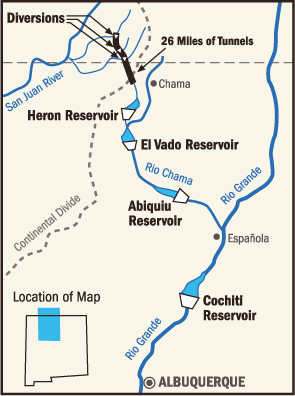

The Rio Grande, bringing San Juan-Chama water to a faucet near you.

Eric Williams ericwphoto.com