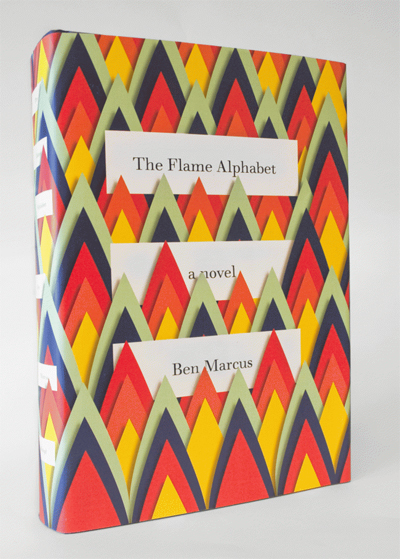

Book Review: The Flame Alphabet

Soap Rendered Useless In Ben Marcus' Apocalyptic Tale

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992