I remember sitting in a classroom and learning about western culture and feeling no proper representation of myself within it./ I wish I knew how to break apart this image of the united states of america and the human body nailed to a wooden cross. I wish I knew how not to remember the american flag.Demian DinéYazhi’

The poison in the pollen/ is poison in our colony is poison/ in your children. Honey, tell me:/ Was your breakfast sweet? Honey,/ when this colony collapses into a pool/ of Yellow Black and Brown honey,/ the women are always the first to go./ I close my wings and hit the ground./ I open my wings and my colony/ drops dead. I close my wings/ and every flower at my funeral/ begins to grieve.Jess X. Chen

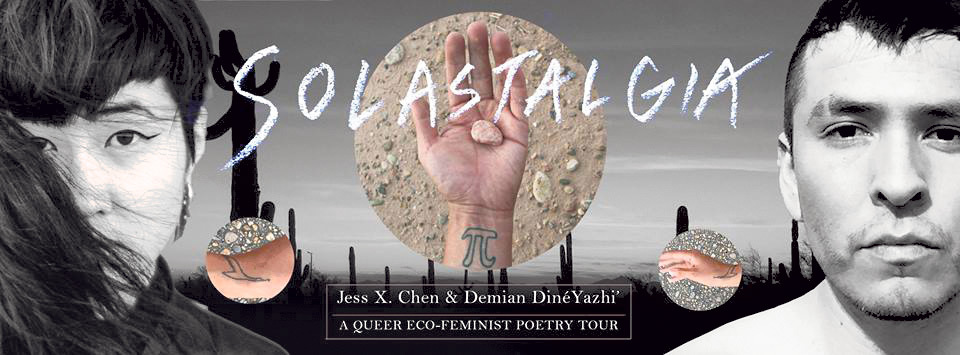

Demian DinéYazhi’ and Jess X. Chen are two multi-disciplinary artists probing with their words the hurts of ongoing environmental degradation, colonization and the myriad injustices that thousands of people struggle against daily. During the month of May, the two are setting out together on a poetry tour called Solastalgia beginning in Los Angeles and traveling eastward, ending in New York. On Monday, May 9, the two will share their queer eco-feminist poetry at the Tannex beginning at 7pm sharp, followed with a performance by the unrelenting electro-punk duo, the Discotays. DinéYazhi’ and Chen were kind enough to exchange some emails with me as they prepared to set off on the West Coast leg of their tour.

Alibi: Can you elaborate on the definition of “solastalgia?” What does it mean and what does it look like to you personally?

Demian DinéYazhi’: Like the homesick sentiment that is attached to that of nostalgia, solastalgia is tied to concepts of solace … and the suffering one encounters when their home environment is in distress. However, unlike homesickness, the person has not left their home or homeland. People speak of this post-apocalyptic dystopian future on the horizon, but for Indigenous Peoples of the Americas, we are actively engaging in a post-apocalyptic dystopian reality. Our traditional ways have been altered by environmental injustice, genocide, forced relocation and assimilation to Western cultural mores.

Jess X. Chen: Solastalgia means the painted experience when the place where on inhabits and one loves is under immediate threat. For migrants, Indigenous people and people of color, it feels almost as if this is a constant state of being. As a second generation Chinese-American whose parents escaped poverty and the violence and silencing of the Cultural Revolution in rural China, I have inherited an inter-generational trauma of feeling like every semblance of home is under threat of being taken away. When my parents migrated, they soon divorced and I followed my mother to America where she changed jobs and moved over 12 times due to economic instability. These constant migrations became embedded in my body and my sense of time. On top of this, Mother Earth is continually driven to collapse by colonial forces, and thus solastalgia becomes a term for our time, but especially for the Indigenous and Islander communities most affected by climate change. A feeling of transience and of fighting to preserve every home and community and love I inhabit permeates into the way I live and love and move about this world. This is what my work is about and what this tour means to me.

How do words challenge?

Chen: The tongue of our colonizer is the only tool we have to give name to our peoples’ traumas [and] our undefeatable resilience in a way that can be understood in America. Sometimes literacy and education become the most intimate and accessible tools to challenge colonization…

DinéYazhi’: Words have the potential to create really bizarre and profound imprints in human history. They have fueled political revolutions and have been re-contextualized, deconstructed, abused and revered since the dawn of language. They are such powerful tools for self-expression. There should be more care and patience when we develop our own sense of language and expression.

Does art have the ability to empower communities? How does it function on a large scale in your eyes? And conversely, how does it function in your life?

DinéYazhi’: Art and design have empowered communities since human existence. Humans have left their marks on canyon walls and built massive structures that we still marvel [at] centuries later. Art has [been] … a powerful tool for religious, corporate and political propaganda for just as long. Yet, it has also become a marker of human intelligence, vulnerability, desire and our ability to utilize our imagination to unbelievable heights. Personally, art has become a tool for resistance, resurgence, reclamation and medication. Honestly, as a person who deals with anxiety on a daily basis, art and survival are synonymous for me.

Your work frequently explores the impacts of colonization, capitalism and environmental ruin. How do we resist the impacts of these things?

Chen: I think the most important thing is to empower diasporic and Indigenous communities with the tools to imagine a world without capitalism and colonial violence. Only when when we know what such a world could look and feel like can we begin to create it within our individual lives … I recently lead a mural workshop with 15 migrant girls of color in downtown LA and we painted a 70-foot mural together. The mural creates a portal into their collective migration story, as each of the girls’ families migrated from Latin American to the US. We created solidarity with the girls and the endangered yellow-billed cuckoo, [a bird] that has been making the same migration journey … which is also depicted in the mural. If we can imagine a future where our stories are visible and monumental, then we can teach the youth in our communities the tools to build that future. The future belongs in the hands of youth, so youth organizing is inseparable from the resistance of colonization.

Demian, how did growing up in Gallup inform your work? What have the communities, cities and landscapes of New Mexico taught you?

DinéYazhi’: Growing up in Gallup has had a profound impact on my work … It can be such a cruel place for someone who isn’t white, heterosexual or male. As far as art and creative practice are concerned, I wasn’t interested in making Indigenous art that perpetuated the commodification of our culture. I didn’t want to get stuck in the insincere Santa Fe thing. Actually, it’s not just Santa Fe, it’s all over New Mexico. White businesses continue to profit off of Indigenous art and culture without properly investing in our communities and [the] evolution of our unique cultures. Through art, poetry and curating events, I am able to support my communities in Portland, New Mexico and Diné Bikéyah (the Navajo Nation) while disrupting mainstream “American” culture.