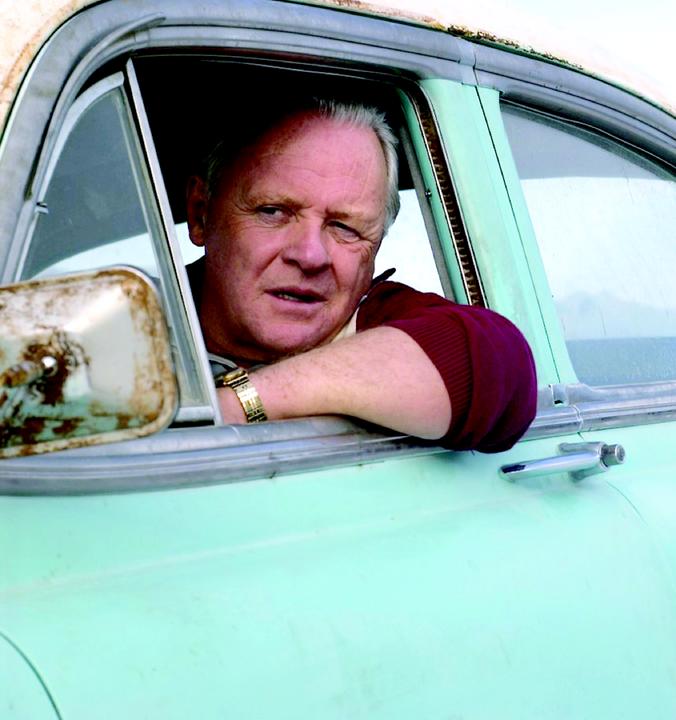

Sir Anthony Hopkins headlines as real-life gearhead Burt Munro. Burt–something of a local legend in New Zealand–was a slightly dotty, mildly rebellious but ultimately lovable old codger who spent the bulk of his life tinkering with an antiquated 1920 Indian Scout motorcyle. His goal was to build the fastest vehicle on two wheels. Donaldson's film picks up in the mid-'60s when Burt was on the verge of his lifelong dream–traveling to the Bonneville Salt Flats in America to test out his creation.

With the help of his many friends, Burt scrapes up just enough dough to get him and his beloved motorcycle to Los Angeles. There, Burt's a bit of a fish out of water. But, thanks to his friendly nature, Burt soon wins enough pals to get him on his way to Utah.

Lightweight and terminally goodhearted, The World's Fastest Indian follows Burt on his episodic quest to reach the Salt Flats. (Think The Straight Story, but with a nitro-fueled motorbike instead of a lawnmower.) Our geriatric hero befriends transvestites in Hollywood, meets a real Indian in the Southwest desert and shares a bed with a lonely widow (Diane Ladd) in the middle of nowhere. There's very little doubt whether or not Burt will achieve his goal. But the film throws enough obstacles in his path that you actually begin to worry about the nice old coot.

Eventually, of course, Burt arrives in Utah, just in time for Speed Week, when the desert is crowded with gearheads and speed freaks. Although he's finally surrounded by like-minded people, the Quixotic nature of Burt's quest finally sinks in. Amid the powerful, high-tech machines of Jet Age America, Burt has introduced a rickety, 40-year-old chunk of scrap metal. He's using a champagne cork for an oil cap. Unable to afford real slicks, Burt has cut the treads off his tires with a kitchen knife. Who in their right mind would let a senior citizen pilot this thing at 200 miles an hour?

Hopkins has more than established his mettle as an actor. He certainly has nothing to prove here, and the role wouldn't seem to offer all that much of a challenge. Burt is just a simple, ordinary guy with a dream. That doesn't stop Hopkins from acting his ass off. Bending his Welsh accent to kiwi slang, giving Burt a humble, halting manner of speech and affecting the engine-addled fellow's slight case of deafness, Hopkins has created a character as full, rich and unforgettable as any in the actor's career. Perhaps, freed from the burden of playing villains or heavy dramatic roles, Hopkins saw the opportunity to channel some of his good-natured glee into Burt. Whatever the case, Hopkins looks like he's enjoying himself immensely.

The World's Fastest Indian could easily have been a manipulative, cornball “feel good” film. And it is. But it's so perfectly done that any missteps are instantly forgiven. Moments that would–in any other film–be dubbed hokey are here pulled off in such a heartfelt manner that disbelief is simply not an issue. Part of this is due to Hopkins' disarming performance and part is due to Donaldson's real love for the subject. (Donaldson made a documentary in 1971 called Offerings to the God of Speed about the then 72-year-old Munro and has, obviously, been brewing this dream project for some time.)

Admittedly, there are moments when the film threatens to spin off into cartoonish Crocodile Dundee territory. The beginning and the end are certainly stronger than the protracted middle. But, like that Indian motorcycle fishtailing at 200 miles an hour, the film rights itself whenever Hopkins sticks his head up. Ultimately, this “never say die” drama succeeds in one of the most admirable goals of a biopic–introducing audiences to a little-known historical figure and making us think, “Gosh, I sure would like to have met him.”