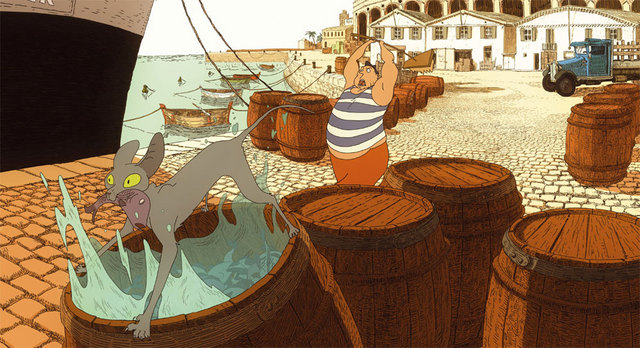

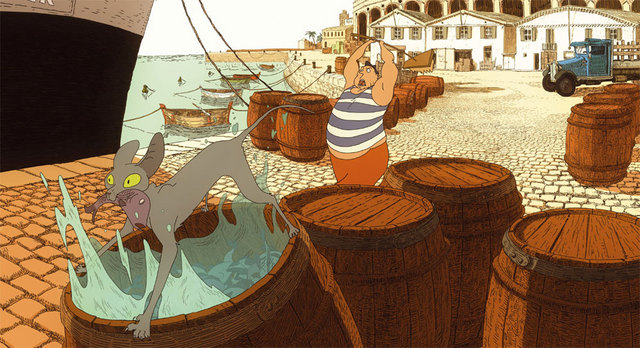

Film Review: The Rabbi’s Cat Gives Animated Treatise On Middle Eastern Religion

Arabesque Animated Fable Offers A Feline’s Take On Middle Eastern Religion

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992