Talk Talk

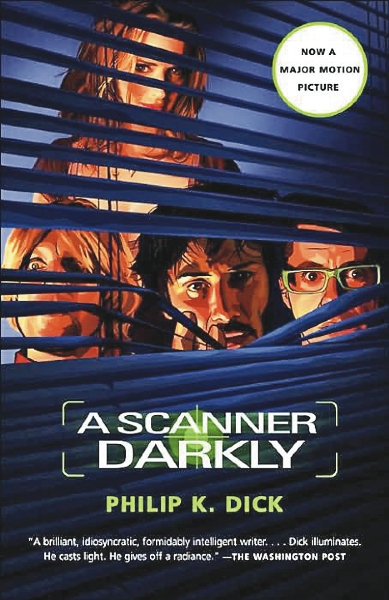

A Scanner Darkly

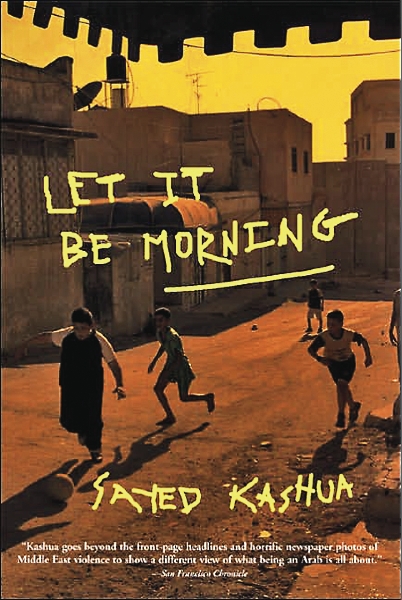

Let It Be Morning

The End Of California

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992