Words On My Lips

An Interview With Beverly Bell, Author Of Walking On Fire

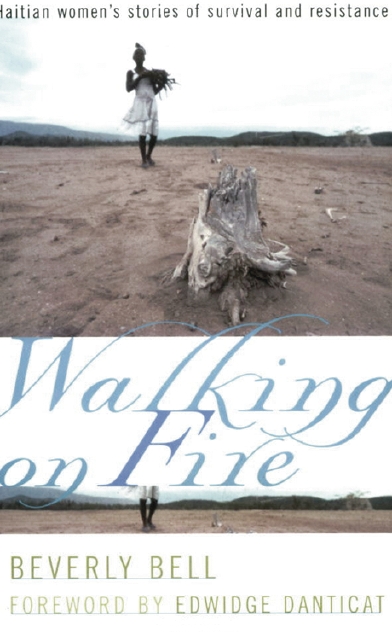

Beverly Bell with Simone Alexandre. Alexandre, who died last year, is called Louise Monfils in Walking on Fire . Photo courtesy of Megan Bowers, Taos News .

Courtesy of Beverly Bell