Give And Take

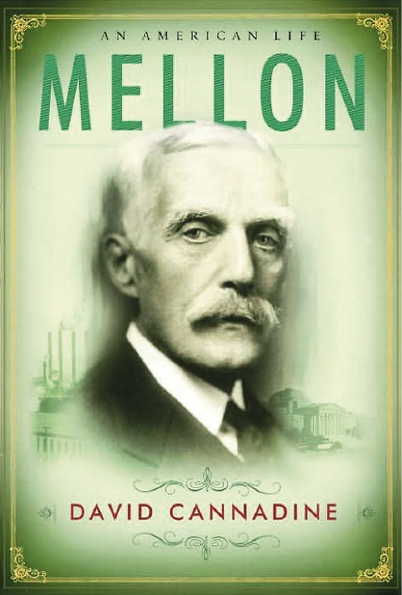

Mellon: An American Life David Cannadine(Alfred A. Knopf, Hardcover, $35) Carnegie David Nasaw

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992