Film Review: The Art Of The Steal, An Eye-Opening Introduction To Art Crimes

An Eye-Opening Introduction To Art Crimes

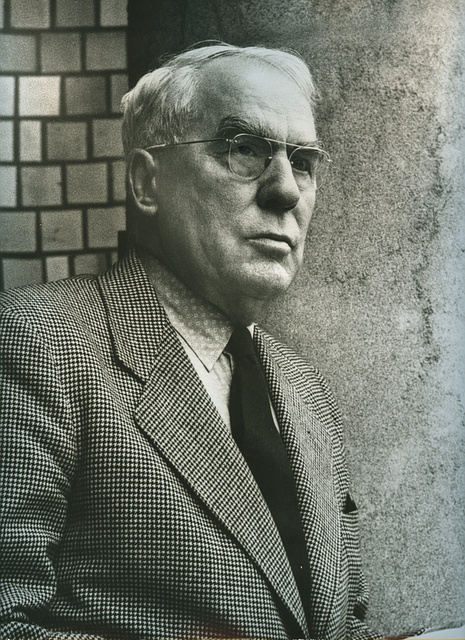

The man

the myth: Dr. Barnes

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992

The man

the myth: Dr. Barnes