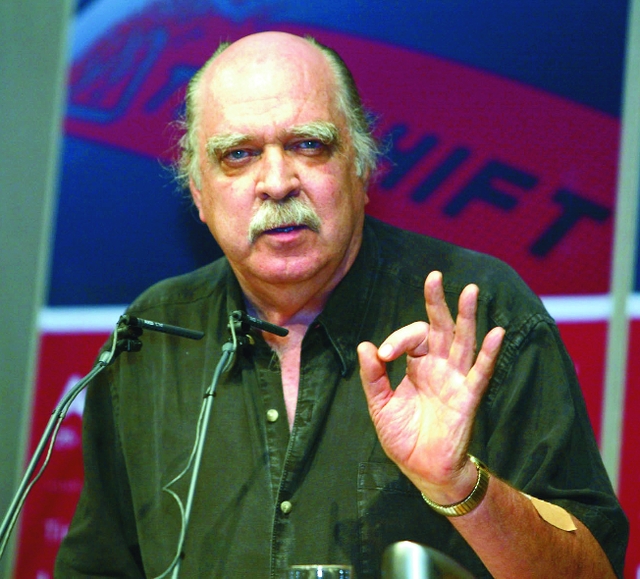

What’s scaring people in the world today, says media theorist Gene Youngblood, is a lack of confidence. "People say, ‘Wow, I’m so depressed. Everything sucks. God, the world is so messed up.’ What people are really saying is, ‘We don’t have the knowledge, and therefore we’re not going to do anything about it. That’s what’s really scaring people." That’s why Youngblood, a professor at the College of Santa Fe, lectures on how people can reconnect and resocialize themselves in a genuine way. His talk, “Secession from the Broadcast: The Rise of Democratic Media,” is part of Bryan Konefsky’s "Experiments in Cinema." The Alibi had a chance to discuss with Youngblood matters of media, free press and how The Broadcast stifles our ability to imagine an alternative world. First off, what’s "The Broadcast"? All corporate media and the culture they create. Don’t say "the media" anymore. Don’t say "corporate media." Don’t say "big media." Don’t say "dominant media." Say "The Broadcast." The culture it creates is the most important part of that. Why rename it? I’m doing it in the same spirit and for a similar reason that feminists back in the ’70s offered the word "Ms." to the world. The use of language in that way is extremely powerful, right? It says something. When you say "the media" or "corporate media" and all that, it’s kind of like there are these things out there, institutions or channels or something. When you say "The Broadcast," that’s more environmental. It carries an Orwellian connotation. It’s some dominant environment that engulfs us. We live in The Broadcast. When you say a "more democratic media system," what does that mean specifically? One has to first acknowledge that the dominant media system is not democratic. The way we were talking about it at that time [the late ’60s], the very logic of it, meaning that it’s a centralized one-way mass audience communication system, is just by definition not democratic. I think that’s kind of obvious. Although, as obvious as it may seem, 99 percent of the people didn’t think that. They just accepted it the way people accept everything. We thought a democratic system would not be a centralized one-way mass audience marketing system designed to turn the nation into an audience that they deliver to the advertisers, but rather it would be a de-centralized two-way special audience conversational network.We were talking about primitive stuff, like public access cable, which we all know never really achieved the kind of presence in our society that we’d hoped it would. Does the Internet approach the more democratic media system you envisioned in the ’60s? Way more than we envisioned. My talk is about the fact that there exists now a fully democratic media world in which one can live 24-7. You believe it’s up to the individual to create her own free press using careful selection of information feeds. What should we consider when selecting? This is why I brought up a utopian myth of a communications revolution we were thinking of in the ’70s. If you propose a decentralized two-way special audience conversational network rather than a centralized one-way, you would have all these channels. They were saying, "Oh, there’s going to be, like, 500 channels on cable." If the thing was truly democratic, they would have all different voices and continuous, uninterrupted, noncommercial access to all voices. There ain’t going to be no "TV Guide" telling you at 7 o’clock, you can listen to them all. You would have to select amongst all those possibilities the channels that interest you the most, that reflect the kind of world you want to live in, the kind of person you want to be. By definition, this fantasy implies you would have to recognize its potential and then you would have to work to find those voices, find those channels and put together a set of channels that would be the media world in which you live. Isn’t that a little impractical? I don’t know. I’m living in it. Why is that impractical? Think of literature. There’s endless writings of all kinds from the history of human beings expressing themselves in literature. It’s all there. Is that impractical? What’s impractical about that? You go out and read those books. Why should people care about this? The subject that we’re talking about is the most important subject, period. It’s more important than anything. It’s more important than global warming. It’s more important than nuclear war. It’s more important than any of those problems because it’s the media and the culture it creates. The culture created by the dominant media determines for most people most of the time what’s real and what’s not, what’s important and what’s not, what’s good and bad, right and wrong, what’s related to what. In other words, it constructs reality for most people most of the time. It determines what you know or don’t know and therefore what you can and cannot think about, what you can or cannot come to desire. You don’t choose a dish that isn’t on the menu. It determines who you think you are.

Gene Youngblood lectures at the Guild Cinema on Sunday, April 15, at noon. Tickets are $4 for students and $5 for everyone else. See Bryan Konefsky's "Experiments in Cinema" at the Southwest Film Center on UNM campus from 6-9 p.m. Friday and Saturday. Tickets are $3 for faculty and $4 for general admission.