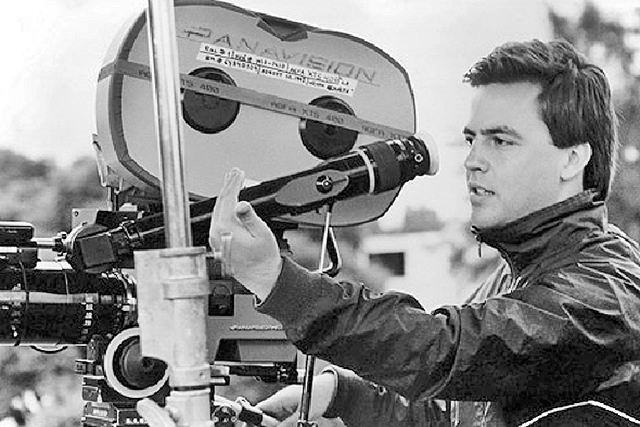

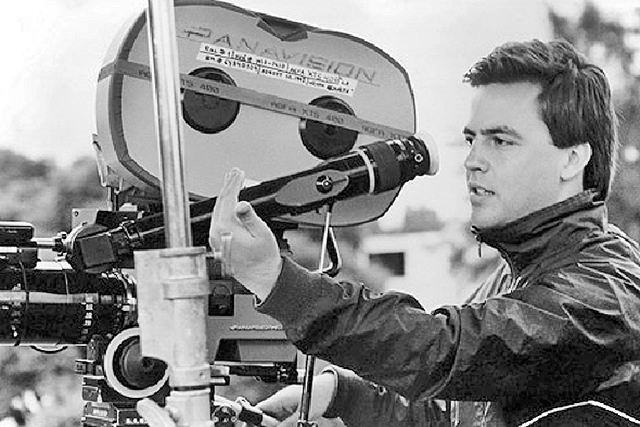

These days, Mexico City-born filmmaker Salvador Carrasco is an instructor at the Los Angeles Film School. Back in 1998, he made his feature film debut with the epic historical drama The Other Conquest (La Otra Conquista) . At the time of its release, it became the highest-grossing Mexican film in history. The Other Conquest tells the epic story of Topiltzin (Damián Delgado), an Aztec scribe who survives the infamous massacre at the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan, carried out by Spanish conquistadors in the year 1520. Topiltzin is shipped off to a Catholic monastery where his fate falls under the control of the conflicted Friar Diego de la Cortuña (José Carlos Rodríguez) and the brutal military leader Cortés (Iñaki Aierra). Topiltzin resists conversion to the Catholic faith, but eventually finds a spiritual connection between the Blessed Virgin Mary and his own Aztec mother goddess. Has Topiltzin given up his culture, or has he found a secretive way to keep his people’s faith alive?Now, after nearly 10 years, Carrasco’s film—one of the first to tell the story of Mexico’s conquest from a Native perspective—is being distributed in America. The busy filmmaker, who is currently in preproduction for the sequel to Dances With Wolves , was good enough to chat with us from California on the eve of his first film’s big Norte Americano release. How did this story come to you? Why did you decide to use it for your directing debut? It has a lot to do with being Mexican, of course. Since I first had use of both consciousness and conscience, I’ve been thinking about these things. I was born and raised in Mexico City. You just step out on the street there and you see things around you that make you wonder—like social injustice and class disparity and the plight of indigenous people and so forth. You hear things in school that you question, such as that the Spaniards arrived and the Indians were happily converted overnight. Really, I think that even as a child you start wondering about this and say, “Wait a second, I’m not buying this. I don’t think it was quite like that.” These were sophisticated civilizations. There must have been resistance to the conquest. I’m sure there were people who struggled to preserve their cultural identity, their beliefs and their ideas. And yet I was being taught the opposite. That was very troubling. It became even more troubling, the fact that there weren’t any movies about this. I think it’s a subject matter about which there should already be a hundred movies. So when I was in college at NYU, I started thinking about my first film. I thought, this is what I’d really like to make a movie about . I felt absolutely passionate. I felt very strongly about the subject matter, and I wanted to tell the story of that cultural resistance. But at the same time, acknowledging the historical reality. It’s a very complex phenomenon. Because on one hand, Mexico—and all of Latin America, for that matter—is profoundly Catholic. On the other hand, there was a struggle to preserve the Aztec identity. So how did these things merge? What were the junctions? What were the challenges? It was just a fascinating subject matter.Of course, the more I researched, the more I read about it, the more questions would arise. That’s some of what I’m trying to do with the film. It’s a film that’s meant to be thought-provoking. It’s meant to pose questions. I don’t think with this kind of film you can give the answers. What I would like is to engage the audience in a dialogue. I think it’s very important for us as Latinos to look at ourselves in the mirror and see where we come from, so we start understanding where we’re heading. Another thing that I think happens with this kind of story is that it’s not specifically Latino. I really think it’s a universal story. I think that’s why this really now feels more relevant than it was some years ago, because of everything that’s going on in the world today. The film came out eight years ago in Mexico and was a huge hit. How do you think it will be received today in America? Well, we did have a taste of it back in 2000, because it came out in Los Angeles and it did great. It did great both at the box office and with the critics. Fortunately, it got rave reviews. It made about a million dollars at the box office, which is terrific for a so-called “foreign film.” We were planning on doing the nationwide expansion of the film and the distributor ceased operations. And for reasons that had nothing to do with us, it couldn’t be done.So we were very excited, there’s this offer now from Union Station Media to at long last do the nationwide release of the film. I’m optimistic, because what I’ve witnessed over the years is that the film tends to resonate with people, that it does strike a chord. I think people feel it’s an honest movie, that it’s not sensationalistic. This one is not about chopping heads and tearing out hearts and that kind of exoticism. I think people connect to a more spiritual approach. Also, I think people respond to the fact that it’s not about “the goodies” and “the baddies.” It’s not really passing judgment, it’s not telling you what’s good and what’s bad. It’s presenting this set of events that were very complex and it lets you participate and draw your own conclusions. People always ask these questions: Was [Topiltzin] really converted or was he just pretending? Did he embrace the Virgin as the Virgin or did he just recover his own Aztec mother goddess? Well, exactly . These are the questions that I ask myself, not just about this character in the movie, I ask those questions about my country and my heritage. Do you think there’s still this question of national identity in Mexico, whether the ties are with Spain or the indigenous peoples? I think so, absolutely. I think also in the U.S. it’s an ongoing debate. We look at ourselves in the mirror and it’s like, “Who am I? Where do I come from? How come on the one hand we have dark skin and on the other we speak Spanish?” Sometimes we feel indigenous, sometimes we deny our indigenous roots. It’s very, very complex. And I think it’s very, very much a story about today. I think that’s the whole point of making a period film, by the way. If you’re going to make a period film, it had better speak about relevant contemporary issues. There’s quite a lot of controversy these days, certainly in the wake of Mel Gibson’s Apocalypto , about the accurate depiction of Aztec culture—whether or not they even practiced ritual sacrifice. How did you approach that subject? I did very, very thorough research. It was over two years of doing research, very methodical, very systematic: the original indigenous chroniclers starting in 1528 and the indigenous texts of the late 16 th century and then Spanish chroniclers. I really took this very, very seriously. Because it’s my history, my roots, my blood. The conclusion of the thorough research I did was what you see in the movie. Now, mind you, yes, there is a human sacrifice in the movie; but really I want people to see it and understand it for what it is. It is part of a religious ritual. You saw the movie. You remember the [sacrificial] princess. It’s something she wills. She wants to join the mother goddess. It’s a kind of self-sacrifice to redeem the community, and we show it with that human dimension. I think it’s very, very different to the depiction of human sacrifices that we have, say, in a movie like Apocalypto . I think it’s a whole different ball game. I’m not saying it’s better or worse, I’m just saying it’s different. I took the research very seriously, and I only show things in the movie that I can back with not one but many resources throughout the centuries. Also, because there are so few movies about this, I knew that the movie would be seen in colleges and by academics, by people who know more about this than I do. I wanted the movie to be respectful toward them as well. For instance, it was very satisfying for me that the person I consider the world’s leading eminence on Aztec culture, Dr. Miguel León-Portilla, who wrote La Visión del los Vencidos , he saw the film in Mexico. At the end of the film, he just stood up, he was deeply moved, he had tears in his eyes and he said, “You nailed exactly what this was about.” If Dr. León-Portilla had said, “You missed the point,” I would have taken it seriously, because I so much respect him. I really took it seriously in terms of the research. For instance, everything Cortés says in the movie, every line, comes from one of his letters to Charles V. I don’t make up things for these characters. I really wanted the film to be authentic, to be believable and to be respectful of my culture. The title of the film, The Other Conquest , seemed to me to be talking about a spiritual conquest as well as a physical one. Is that the way you saw it? I like the title, because it has that sort of multiplicity of connotations. My favorite one is that it’s the other conquest which has to do with cultural resistance. Because in the end, Topiltzin the protagonist, he recovers his mother goddess. Except now she has a new face. For me, that’s very important, that Topiltzin and Friar Diego were really talking about the same thing. But unfortunately, we kill one another because we call our beliefs by different names. Is there really a great difference between the mother goddess and the Virgin Mary? Those are the questions I would like people to ask. Most Mexicans today, why are they so profoundly Catholic? Well, because we didn’t cut the ties with the world before the Spaniards arrived. There’s a lot of synchronism, a lot of merging of beliefs. That’s why we’re such a complex and fascinating culture, I think. But to me, that’s what the other conquest is—the way the indigenous people appropriated the symbols of the conqueror. They made them their own, and that’s why they can have their own personal, direct relationship with these gods in their own terms. As a result of that, we have the indigenous Virgin of Guadalupe, for instance. So, when you see a dark-skinned indigenous-looking Virgin Mary, I think it’s pertinent to ask, “Wait a second, who conquered whom?”Sure, we all know there was a military defeat, it was a genocide, they had better weapons, whatever. But I think, spiritually and psychologically, it was a different story. I think there was another conquest, a conquest that has a lot to do with how the indigenous culture managed to survive and preserve their beliefs and cultural identity. See, when I was told in school that the Aztecs just disappeared, that they were annihilated, I didn’t buy that. I think that they survived. But they had to survive in creative and ingenious ways, because when they take everything away from you, you have to become ingenious, you have to become creative. You have to sometimes worship your own gods even though they have a new face. And that’s exactly what the archaeology proves. For instance, when they were digging the subway in Mexico City, under the Spanish columns they found the faces of Aztec gods. Imagine the power of the belief of these Indians who are building the Christian churches, that they find a way of putting the reliefs of their own gods on the base of the columns. That’s the part that fascinates me. Now that the film is hitting America, are you looking for more cross-cultural projects in Hollywood? I’m based here now, I live in Santa Monica. What I’m looking for is good stories. Something that is a good story inherently but that also has a more universal dimension. It might be something that takes place in Mexico, in the U.S., in Europe. I want it to have a human dimension more than anything else. That’s what I’m on the lookout for. I’m already developing a couple of things. I’ve been attached to direct the sequel to Dances With Wolves,

which I hope materializes. I really believe in the power of film to tell meaningful stories that affect people emotionally. It’s amazing that you can make your film and it can be seen by millions of people. I think that gives filmmakers a tremendous moral responsibility.

The Other Conquest opens this Friday in limited release.