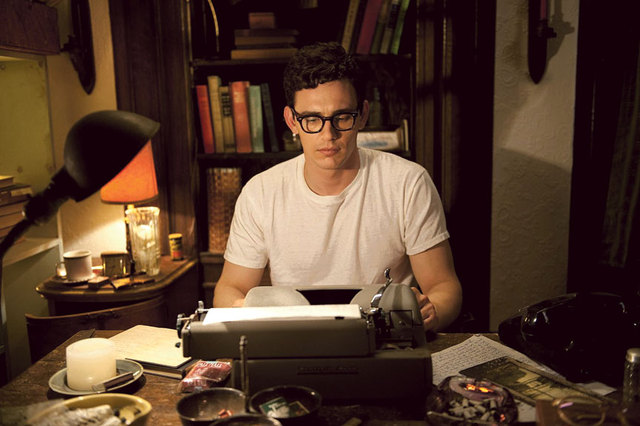

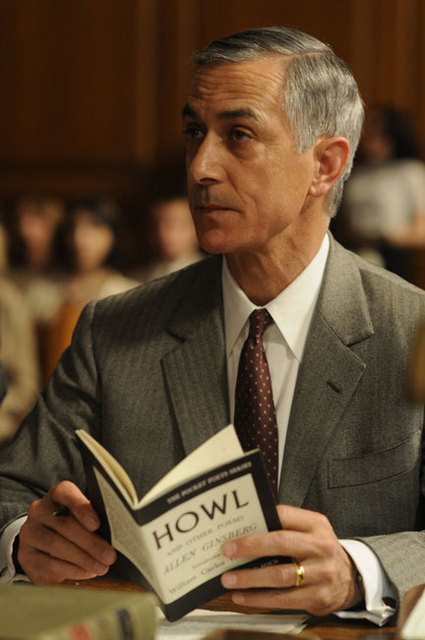

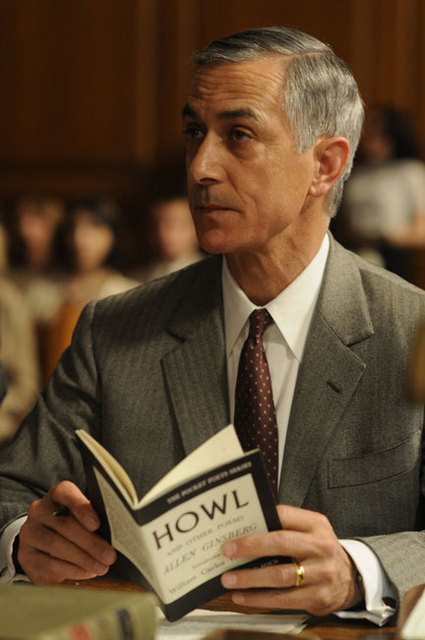

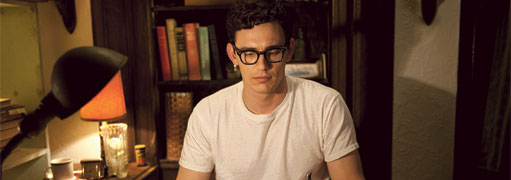

Film Review: James Franco Sees The Greatest Minds Of His Generation Destroyed By Madness In Howl

When Is A Biopic Not A Biopic?

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992