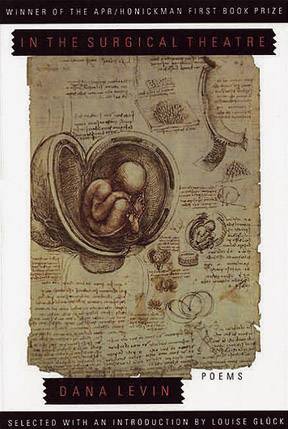

For 11 years, poet Dana Levin taught creative writing at the College of Santa Fe. Though CSF has managed to come back to life in an altered form after its near-total collapse, Levin has moved on. She is now the new Russo Chair of creative writing at UNM. Levin’s first book, In the Surgical Theatre, won the 1999 APR/Honickman First Book Prize, among many others. She is also the author of Wedding Day. Her third book, Sky Burial , is slated for a 2011 release from Copper Canyon Press. Levin sat down with the Alibi to talk about living the vida loca of a poet and professor. She will be at the Church of Beethoven on Sunday, Oct. 11, and Wednesday, Oct. 14. You can read our extended interview, and bear witness to Levin’s spectacular Louise Glück impression, online at alibi.com. What do you see as the connection between being a poet and being a teacher? Most poets teach; is that natural? How has that evolved? That’s just the way things are now. One common analogy that people like to make is that artists have always relied on a patronage system and that the university has become the central patron of the arts. Not just poetry, but dance, theater; art forms that are not necessarily lucrative. Artists have found homes on university campuses. I’m really split in my thinking about it. On the one hand, just because you went and got an MFA doesn’t mean you’re going to be a great teacher, because teaching is an art. … On the other hand, I think that it’s honorable and necessary to bring the word of art and imagination to American students. We, our culture, is ambivalent about the arts. If you make a lot of money, great. If you get a lot of fame, great. But, in general, I think the culture has an underlying suspicion of the arts, just like it has an underlying suspicion of intellectualism. You know, it’s the populist strand of the American character. The great thing about working with undergrads is that their pure in their engagement with poetry. They’re not thinking about a career, they’re not necessarily thinking about getting published, and so it feels great to be with students for four years and help them enter creativity. At the graduate level, it gets more complicated. If they’re very serious students, what they want is a career in publishing and maybe a life in teaching, and there’s no guarantee that the degree will help them access either of those things, though programs can do their darndest to help them in those regards. As a teacher, what have you learned about your own poetry? One thing teaching has taught me is that good teachers are generous teachers. What I mean by that is, you can get a student poem in front of you that someone else thinks is a total disaster, but if you have a spirit of generosity in your teaching, you don’t view it as a disaster, you view it as raw material and you see something, and you offer a vision to the student of a way to proceed with this raw material that they can take or leave. That spirit of generosity counteracts the impulse to quickly judge whether something is good or bad, or whether a poem is hopeless or not. Bringing that to my own writing is very helpful because I’m endlessly, mercilessly judgmental, and that’s not good if it comes up when you’ve only written, like, a stanza. If you’re sitting there proceeding, This sucks, This is shit, I don’t want to do this … this spirit of generosity has to come forward from yourself to your own work so you can allow the poem to blossom into whatever it wants to blossom into. I’m always telling students, Don’t worry about it. In the next draft, you’ll fix the issues, that kind of stuff. So, having to remember to bring that to my own life [works].Teaching has also helped me be a better reader of poetry. And to have a constantly developing sense of the relationship between what I would call form and feeling. I don’t want to call it form and content because we’re not writing about something, we’re writing a response to something. I mean, content is content. So, to say that William Carlos Williams wrote about a wheelbarrow is not accurate. What we’re really saying is that William Carlos Williams was moved to write from an encounter, perhaps, with a wheelbarrow. And so, it’s the act of response that is what creates the poem, so that’s why I like to say form and feeling. Anyway, always developing a sense of the relationship between form and feeling and being able to articulate it and manipulate it. If I proceed like Ginsberg’s "Howl," where every line begins with the same word or the same kind of sentence, I’m going to get a really driving energy going. And to be able to know that rather than just stumbling upon it, I find that satisfying and interesting. What’s the importance of mentorship for a poet? Mentorship is really important. I was so blessed in my development to have teachers that were very encouraging. I came from a first-generation American family. I was the first person in my family to go to college. My parents came from an immigrant mindset, so, Poetry? What the hell is poetry? You need to go make a living, and all that kind of stuff. So it was really important to have teachers at the undergraduate and graduate level who were like, You should do this. You have the capacity to do this, and there’s a life for you in it. That’s the thing I didn’t know about. Mentorship is important in terms of giving a student permission to be an artist. Just as the American character has ambivalence about the artist, many families have ambivalence about their kid becoming an artist. To find permission and nurturing from a mentor is important. To be introducing them to writers, to books, to be opening the door to the vast world of poetry so that they can encounter as much of it as they want.Mentors are important. They’re not a parent, but they’re more than a friend. They can be an inspirer and a steady hand. I like that aspect of my teaching. You’ve benefitted from having mentors as well. Yeah. The most active mentorship I’m in is with Louise Glück. She picked my first book for the [Honickman 1st book prize] and that was how I met her. That was kind of unusual. People usually assume that the judge has foreknowledge of the person whose book they pick. But I was a stranger to her and she was a stranger to me, not the work, but I’d never met her. No relationship, I’d never studied with her. And she has been an amazing supporter and teacher. She can be extremely harsh (laughs). You show her a poem and she’s like, Oh, this is just Day-nah Leh-vin, you know, going on with her raaap-ture. But it’s OK; it’s like tough-love mentorship. But she’s also funny and generous and has become a friend. I like your Louise Glück impression. Oh, god. She is a stern taskmaster. And she’s been an interesting mentor because, on the surface, our work seems to bear no relationship to each other. Her work is very spare; she’s very stingy with images … but the place where we meet is the deep place, in that we’re both oriented to bringing the mind to emotional and psychological experience, to sort of think through feeling. And so, I think that core, even though we have very different ways of going about it, is where we meet. Who are some of the new poets you’ve been reading? I just wrote a review for Poetry magazine of a book by a poet named Michael Dickman. It’s called The End of the West . I think it’s fantastic. I like what he does with line breaks. I just love this book. Michael Dickman? Yeah. He’s a twin. His brother is Matthew. Who just won the Honickman for All-American Poem. Damn, twins! I dig Michael. And it’s a different book [from Matthew’s]. Current younger-poet poetry, the approach to language is really sort of hyper. Every line is stuffed with stuff. Younger poets are more interested in the lyric poem than they are the narrative poem in general. Michael’s poems are narrative poems that kind of have a spare language pallette. There’s some beautiful moments in there. This isn’t a young poet but I just love this book. Arthur Sze has a new book called The Gingko Light . I think it’s my favorite book of his. Arda Collins has a new book called It is Daylight that I like a lot. But my two current passions would be Dickman and Sze. I’ll have to check those out. I recently read Matthew’s [ All-American Poem] . They’re very different. Michael’s the darker twin, apparently, in terms of the poetry. Matthew’s all, Ecstasy! American poem! And Michael’s, We had a shitty family. That’s interesting to see two perspectives of the same experience. Anything else you’d like to add? Well, I’m very grateful that UNM gave me a job. I’m very grateful that creative writing department has welcomed me there. I like being of service to those students. I like getting to know Albuquerque more; it’s a cool place. You get around. How would you compare New Mexico’s poetry community and opportunities with other places? Oh, I think it’s tremendously lively. For a small state that has a small population, it’s amazing how lively the poetry community is all up and down the state. … It seems like there’s always a lot going on here in poetry. I really love living in Santa Fe because I have access to that kind of community without having to live in New York or Cambridge or San Francisco, and I get the benefit of space but also culture and deep love of words, which I just think is awesome.

Dana Levin at the Church of Beethoven

The Kosmos

1715 Fifth Street NW

Sunday, Oct. 11, at 10:30 a.m.; Wednesday, Oct. 14, at 6 p.m.

$15, $10 students, $5 under 12

(Students $5 on Wednesday)

churchofbeethoven.com