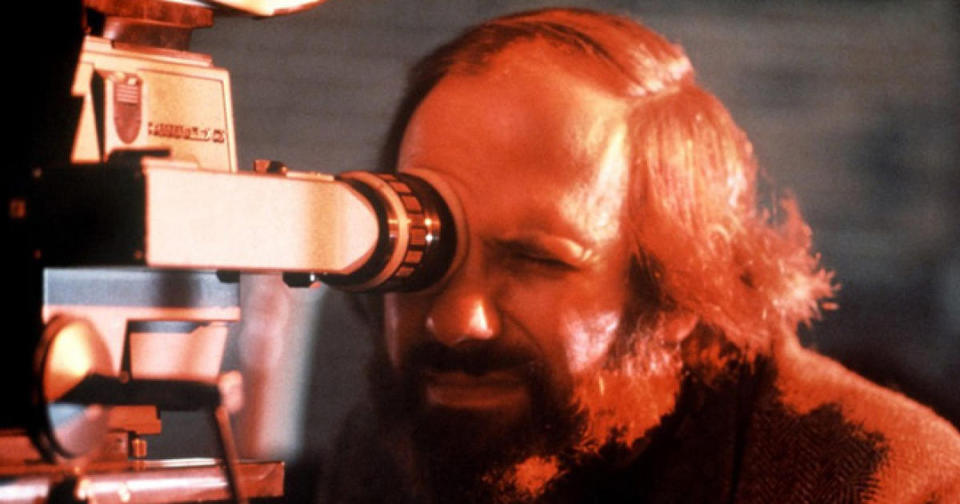

Film Review: De Palma

No Nonsense Documentary Lets Film Industry Icon Analyze His Own Art To A Fault

the myth

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992

the myth