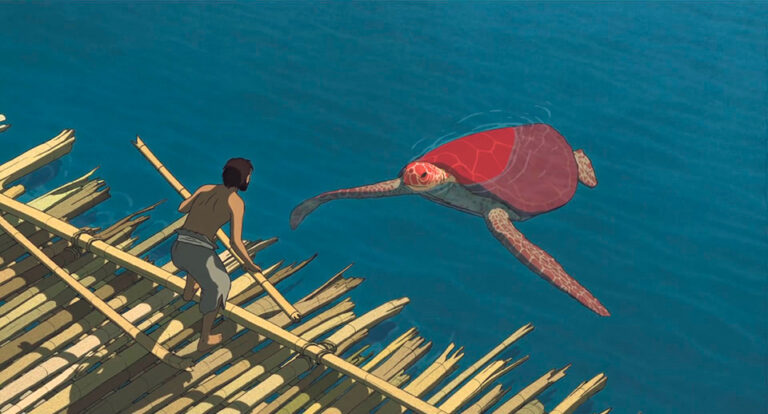

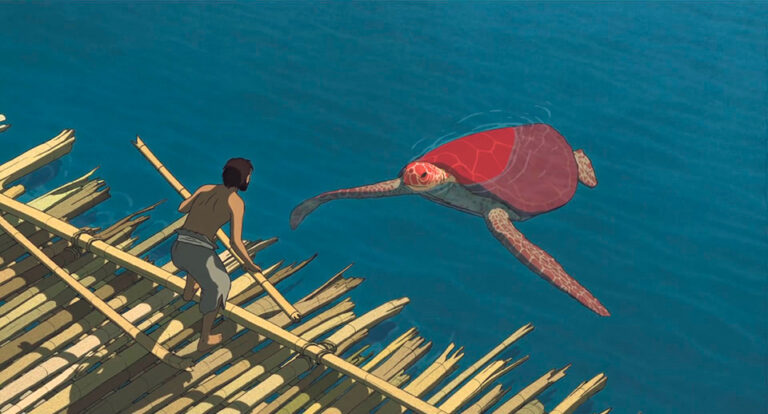

Film Review: The Red Turtle

Silent Tale Of Survival Holds Surprising Depth

“...”

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992

“...”