The United States in 2005? Think again. In the early 1860s, a president who is today almost universally revered for the eloquence of his words and the undeniable majesty of his actions, suddenly emerged as perhaps the most vivid proponent of government control and censorship in American history.

Six months into the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln issued an executive order suspending the writ of habeas corpus, the constitutional protection against citizens being imprisoned without charge or trial. Scores of newspapers critical of the administration were closed down, local officials arrested. Several months later, writes author Michael Kauffman, Lincoln's assault on his foes had even reached into the legislatures of the states: “Thirty-two lawmakers and their sergeant at arms were taken from their beds at night and carried off to prison. No charges were ever filed.”

Lincoln was convinced that he had to take such drastic actions because of the existence in the North of what he called a “most efficient corps of spies, informers, suppliers, and aiders and abettors” who were plotting against the government. More colorfully, Lincoln added that he could not be expected to fight a battle at his front and rear simultaneously.

Whatever the reason, Lincoln's heavy-handedness had the intended effect of greatly silencing his critics. But oppression in a nation weaned on the virtues of dissent inevitably creates dissonance. When Lincoln was re-elected—to the astonishment of opponents who were certain that his handling of the war and suppression of civil liberties had finished him politically—there was a sense, writes Kauffman, that there was now “nothing anyone could do to get him out of office.”

“Well, actually there was one way,” Kauffman continues. “Government sources reported that after the election, newspapers in Richmond began to discuss the idea of assassination.” It was something that had no doubt been contemplated by many, both North and South of the Mason-Dixon line. But for a young man whose rather eccentric family had nourished a legendary passion for liberty, no doubt whetted by an intimate familiarity with the Greek classics, the killing of Lincoln became not only an obsession, but a conspiracy that would ensnarl many who were captivated by the assassin's personality.

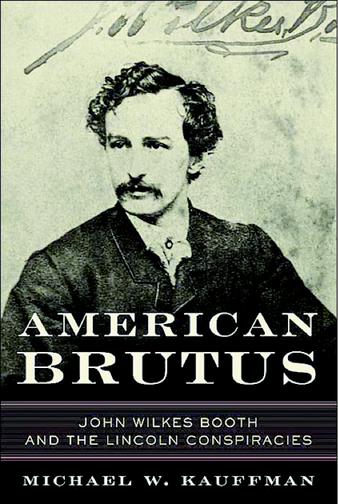

John Wilkes Booth was only 26 years old when he murdered Lincoln. But already he was a national figure, the son of the famous actor Junius Booth, and a worthy interpreter in his own right of Shakespeare's most difficult plays. Handsome and overtly sexual, John Booth beguiled audiences in his time and continues to seduce from the grave: More than 50 books have been written about him, not counting the plays, sonnets and poems he has inspired.

Michael Kauffman's American Brutus—30 years in the making—is only the latest. But surely it is the finest. Sifting through the thick Lincoln assassination files now housed at the National Archives, but also retracing Booth's steps in the extremely active theater world of the early 1860s, Kauffman has produced a solid work of scholarship that intricately explores the explosive political emotions of the era.

Of Booth's guilt, there is clearly no doubt. Through letters to and from Booth, coupled with later courtroom testimony of the many who regarded themselves as his confederates, Booth's enmity for Lincoln was consumptive. Classic among all real and would-be assassins, he wanted only to do something heroic and dramatic, a true final act that would never be forgotten. In this latter pursuit, Booth was remarkably successful.

Nearly two weeks after Booth killed Lincoln, he himself was shot by a soldier south of the Rappahannock River. He died an extraordinarily painful death, the bullet from the soldier's revolver having entered and exited his neck, causing him to slowly choke. Yet to the end he remained convinced that he had done the right thing, whispering to one of his captors on that cold, wet Virginia night many years ago: “Tell my mother—tell my mother that I did it for my country—that I die for my country.”