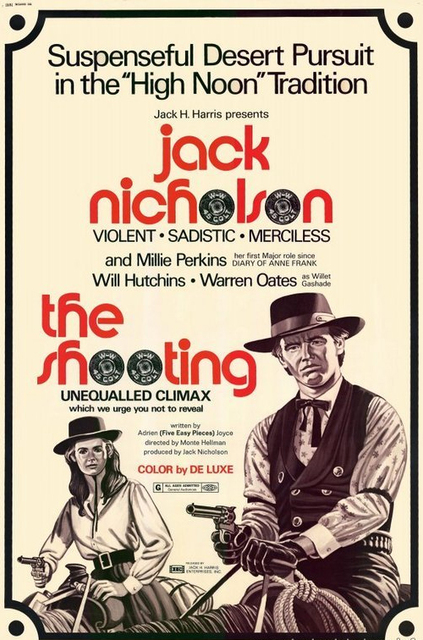

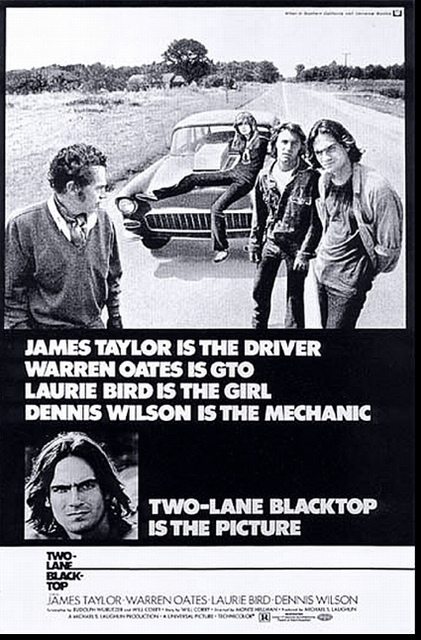

The second annual Albuquerque Film Festival is about to open the floodgates, letting loose five days’ worth of films, panels, workshops and parties. Throughout the weekend, there will be feature films, both local (Rod McCall’s coming-of-age drama Becoming Eduardo, Andrew Lauer’s kiddie fantasy Adventures of a Teenage Dragon Slayer) and national (the Iraq War drama The Dry Land starring America Ferrera, the low-budget indie dramedy Fanny, Annie & Danny). This year’s guest of honor is iconic indie filmmaker Monte Hellman. Hellman launched his career working for B-movie king Roger Corman, starting with 1959’s The Beast from Haunted Cave . Hellman went on to shoot several films with Jack Nicholson, including the gritty mid-’60s Westerns Ride in the Whirlwind and The Shooting . Hellman’s cult following hit its height in the early ’70s when he directed the existential car chase flick Two-Lane Blacktop with Warren Oates, Laurie Bird, Dennis Wilson and James Taylor (the only feature acting roles for the two famed musicians).In addition to screening some of his classic films ( Two-Lane Blacktop, The Shooting, Cockfighter ), Hellman will head a panel discussion on digital filmmaking. He’ll accomplish it all just before jetting off to the Venice Film Festival to premiere his first feature in 21 years, the film noir romance Road to Nowhere . Luckily, Alibi was able to chat with Hellman via phone before his arrival in Albuquerque. You spent almost 15 years working with Roger Corman. Despite his reputation as a cheap bastard, I imagine cranking out films for him must have been an incredible training ground. The obvious answer is you learned to deal with no time, no money and anything else you can think of. Nobody bothered to get permits. For a two-day shoot, you lose the first two-thirds of the first day because you’re sitting around a courthouse getting permits. … You don’t have the time to get the coverage you would like. So, you learn to do things minimalistically. And it leads to either a primitive style or everybody says, Oh, it’s so spare. It’s spare because our pockets were spare. The Shooting was the first film that really put you on the map. What was it about that film that was different? I think it all starts with the word. I had a brilliant writer [Carole Eastman] who hadn’t written, but gave every indication that she could. Against the advice of my friends and partners I decided to go with her. I’m assuming the film was just another B-movie assignment by Corman. It was an assignment in the sense that we made a deal to make two Westerns. But it was not a set project. We created the project from scratch. We were given an assignment that basically let us start with blank pieces of paper. We had to do two scripts [ Ride in the Whirlwind and The Shooting ] and shoot them back-to-back. We had two wonderful writers. Jack [Nicholson]’s a wonderful writer and Carole’s a wonderful writer. Was that just luck for you, or was that filmmaking at the time? I can’t imagine anyone going to a studio today and having them say, “Just start with a blank page.” It was the Roger Corman method. But at the same time, when he saw the scripts that came from the first part of our creative effort, he was appalled. He was ready to cancel the projects. Except for the fact that he had already spent something like $10,000. Being an engineer, he quickly computed that if he canceled he’d lose $10,000—whereas if he made these very cheap movies, there was no way he could lose anything. He kind of shrugged his shoulders and said, OK, go ahead. According to the stories, shooting Two-Lane Blacktop was a very minimalist experience. Just you, the actors and a small crew traveling across the country. Just the opposite. It was the only studio picture I made. It was a huge crew for me; a small crew for studios. But they had these huge studio trucks and big equipment. We talked them out of certain people that we didn’t need, like makeup. But it was the biggest company I worked with. How did that feel? I felt a little bit limited by it. Particularly since we had a director of photography that we didn’t intend to use. He stayed in the hotel every day. We just had a lot of extra people that we didn’t need. Even though we were allowed to make it minimal for that kind of production. The film has become a cult item over the years, but it wasn’t very well known at the time of release, was it? The head of the studio [Universal’s Lew Wasserman] just decided that he didn’t like it for one reason or another. I think he found it politically abhorrent—supposedly in the sense that it was kind of anarchistic and “against family values.” So he was offended by it. He allowed a wonderful associate, Ned Tanen, to go off on his own and go with what they thought was the modern age. They did a series of [“youth”-oriented] films [including Two-Lane Blacktop ], all of which were interesting— The Hired Hand, The Last Movie, Diary of a Mad Housewife . Lew Wasserman decided he didn’t like any of them. Particularly, he decided he wasn’t going to put anything behind releasing Two-Lane Blacktop . Even though a number of theaters were very excited about it, had developed their own advertising campaign, he just didn’t give them any support. So the picture opened in New York without, literally, one single newspaper ad. When I watch your films— The Shooting and Two-Lane Blacktop, and Cockfighter to a certain extent—the word that comes to mind is “existential.” They’re not so much about plot or action as they are about characters trying to define their roles in life. Is that how you thought about them? Usually what I’m thinking is, How do I get through this? No, I think even today nothing that I do is premeditated. I work pretty much from the seat of my pants and the pit of my stomach. I try to tell the story as best I can. In the case of The Shooting or Road to Nowhere , I try to figure out what the stories are if I can—not always successfully. We kinda plow through it, and in the process something comes out the other end that is a little bit unpredictable. Which is something that I like. If I can predict the whole thing and see it all finished, I kinda don’t even need to do it. I’m just as curious as everybody to see what it’s gonna come out like. Do you disagree with people who see the films as existential? Do you think, No that’s too high-minded? No, because I think whatever they figure out is what’s right for them. I want the audience as a collaborator. I give them 80 percent, and I love it when they can put in the last 20 percent. Then it becomes our movie—not just my movie or their movie.

Albuquerque Film Festival Wednesday, Aug. 25, through Sunday, Aug. 29 Events take place at the KiMo Theatre, UNM’s Southwest Film Center, Aux Dog Theatre, Guild Cinema, the National Hispanic Cultural Center and Hard Rock Hotel & CasinoFull schedules are available at abqfilmfestival.com