For Charley, however, the bonding went down not in his backyard, but in a comic book store in New York City, where he and his father, the novelist Peter Carey, used to go Saturday mornings to inspect the goods.

They were interested in one kind of comic—manga—splashily illustrated Japanese comic books that sell by the billions in Japan. One trip became two, eventually leading to Peter Carey angling for a journalism gig in Tokyo to interview Japanese animators.

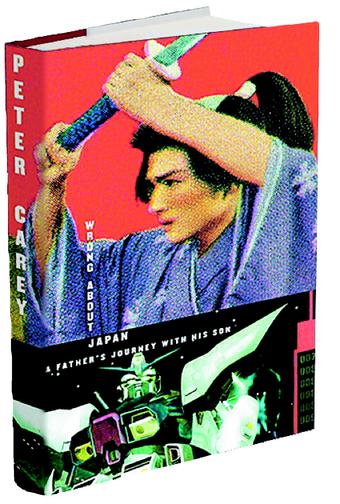

If this were any other duo, the Careys would have wound up with a nice photo album. But since this is Peter Carey, we now have a book, Wrong About Japan, a charmingly comic tale about a father and son's shared experience of cultural confusion in Japan.

Bill Murray and Scarlet Johansen fell in love during their circadian fugue in Lost in Translation. By the time the jet lag fades here, though, Carey and his son have already moved in different directions. Carey wants to see the “old Japan,” of tea gardens, Zen masters and Noh theater. Charley wants to see the new Japan of video arcades, comic book stores and anime films.

Quickly a divide opens up that is part generational, part national. Born in Australia in 1943, Carey grew up playing with Japanese occupation money. His son, however, came into the world during the '80s nourished by American pop culture and globalization theory.

Their differences find a bridge in the form of Takashi, a Japanese boy Carey’s son met over the Internet. Decked out in the latest fashions, with an aura of otherworldly lightness, he agrees to be their guide. Carey's description makes Takashi sound like something out of a Japanese anime film: “In Tokyo's Harajuku district one can see those perfect Japanese Michael Jacksons, no hair out of place, and punk rockers whose punkness is detailed so fastidiously that they achieve a polished hyper-reality. Takashi had something of this quality. He had black hair that stood up not so much in spikes but in dramatic triangular sections. His eyes were large and round, glistening with an emotion that, while seemingly transparent, was totally alien to me.”

Carey's prose in Wrong About Japan often sounds a lot like this passage, with its confectionery swirl of cartoon images and journalistic remove. Whether by accident or on purpose, Carey has found a unique literary anodyne to the world of Japanese anime. As a result, these memoirs are a homage to both Charley and the art form that so captivates him.

Takashi is sometimes around to help them navigate this alien culture. For example, in leading them to meetings with famous Japanese animators and toy designers, he is both emissary and cultural gauge. Later, it is Takashi who steps in to let Carey know he has offended a cultural sensibility.

But other times he is not there and Carey finds himself, once again, wrong about Japan. A man in a restaurant, who seems too much of a cliché to be a gangster to Carey, apparently is one; the sword maker Carey later interviews practically laughs in the novelist's face when he asks if making a sword is a spiritual action.

Reading the book, you sense this is a significant moment for Carey, a necessary boundary to establish. Indeed, after Coppola's film it became rather too easy for Tokyo to be seen as a signifier for emotional estrangement.

In this unlikely little memoir—which, I must add, is lavishly illustrated—Peter Carey puts the culture back in the picture. At the same time, he choreographs an artful emotional tango between a father and son who are trying to not be lost in translation with each other, and mostly succeeding.