I remember the exact moment I fell in love with moving image arts. It was September of 2002, somewhere on the upper spiral of New York City’s Guggenheim Museum. I entered a little room and there, projected on the wall, was Shirin Neshat’s “Passage,” an approximately 12-minute film depicting the funeral processions of Iranian men and women. I happened to walk into the screening room just at the beginning of the film and sat through it twice, unable to articulate what I had just seen and felt. Afterward, I wandered through the rest of the exhibition Moving Pictures in something of a daze.More than a year ago I heard this upcoming SITE Santa Fe exhibition was to feature video art. I have been anxiously awaiting it ever since. The Dissolve , however, a show that features more than 20 works, left me in a very different daze than Neshat’s work and Moving Pictures . Instead of being inspired and filled with joy, my world more open and more complete than it had been before, I wandered out of the building after two hours, sat down with a beer, and tried to realign the aural and the visual.There is some amazing, and potentially transformative, work in The Dissolve, but the show is installed so oddly it becomes difficult to focus on any one. Instead, sounds and the flicker of screens overlap, creating an atmosphere that represses individualism.To be honest, I couldn’t see every work in the show because by the end my nerves were so on edge, so frazzled that I became increasingly angry at each corner I turned. I felt like an epileptic watching a strobe light.The first piece you come across, Hiraki Sawa’s 2003 “Airliner,” sits in the lobby. As with many of SITE’s installations, the lobby piece is one of the strongest, but it suffers from the atmosphere of sound and light. “Airliner” is a short work that consists of images of planes flying over the pages of a quickly flipped-through book. Because of the light that seeps in from windows and doors, despite efforts to minimize the rays with dark fabric coverings, the hand that holds the book is mostly obscured.Assuming that this problem would only exist within the entry space, I bounded forth, excited to revisit the aesthetic of Kara Walker, whose work I also encountered for the first time in that trip to New York eight years ago, and whose work I have come across regularly since. Walker uses shadows to discuss themes of racism and slavery, often including violent rape scenes. The works “Six Miles from Springfield on the Franklin Road” and “Lucy of Pulaski,” both from 2009, drew me in through their powerful imagery. Though more than 25 minutes long, I was committed to sitting through the entirety of the work. But, there was a problem. The sounds from a nearby piece, Jennifer and Kevin McCoy’s “Traffic #1: Our Second Date” bled through the space. While I watched the burning of a shadow-puppet and cellophane Southern town, the sounds of car horns overpowered the piano-based soundtrack. To make matters worse, a couple struck up a conversation with the docent next to “Traffic” and the ensuing echo of a conversation I couldn’t quite hear was so distracting I had to abandon the Walker to penetrate the exhibit further—and hope that in doing so I would find myself alone. Thomas Demand’s “Rain” caught my eye but was even closer to “Traffic,” so I had to remind myself to return to it later—which I did, though a different conversation dominated that viewing as well. Instead, I slipped past Robin Rhode’s “Kid Candle from ‘Memories of Childhood’ ” and Paul Chan’s “4th Light”—both of which looked as if they would be more interesting in the conceptual stage than they were once put onto walls—into a back room that was dominated by fabric walls and fairly bright lighting. Berni Searle’s “About to Forget” was a great way to experience art despite imperfect conditions. The three-channel video projection begins with cutouts of people, traced from photographs. Red paper is dropped into water and, for the next three minutes, color bleeds in abstract swirls. It’s like the artful chaos of slowly pouring cream into a cup of black coffee. The meditative loop drew me in for some 15 minutes as people came and went on the benches next to me.Sadly, the remainder of this room, an egg-shaped enclosure of thin green fabric, held work that was unwatchable. Many of the works were fantastic but the sound from an adjacent piece bled so loudly over that of the piece in front of which I sat, I couldn’t concentrate. “Maria Lassnig Kantate,” by Austrian artist Maria Lassnig, was the worst of these, and the irritating song of the pretentious and narcissistic work overtook everything else. I escaped to The Dissolve’s standout piece, William Kentridge’s “History of the Main Complaint,” a short, charcoal drawing animation that was so alive one could almost see it being drawn as it progressed.Reinvigorated, I sat on the floor, as there was no bench, in front of Avish Khebrehzadeh’s oil painting (“Theater III”) onto which a short film (“Edgar”) was projected. It was beautiful and moving. Khebrehzadeh should be furious that her work has been placed in a section of the gallery that suggests one should glance at it and move quickly on. Anyone who tries to watch it will have their attention drawn to the casino-like lights and clinks of Federico Solmi’s “Douche Bag City,” itself an interesting work but one that so thoroughly ruined “Edgar,” I gave up, breezing past the remainder of The Dissolve .SITE has, in the past, projected video with skill. In The Dissolve , the small space tried too hard and put too many pieces in too close a proximity. If half the works were removed, installers could have properly placed each work and created an enjoyable, rather than hostile, environment that makes any true experience of inspiration impossible.

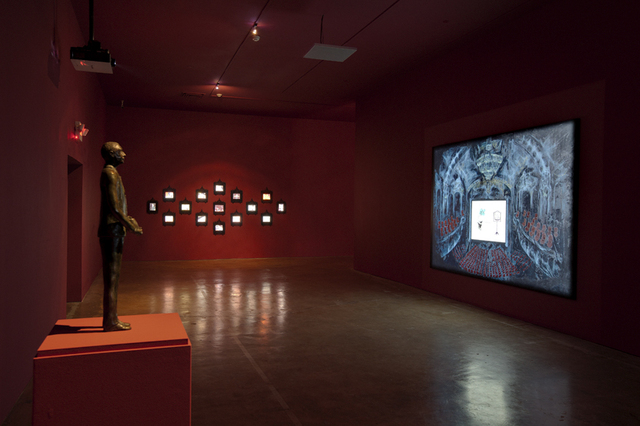

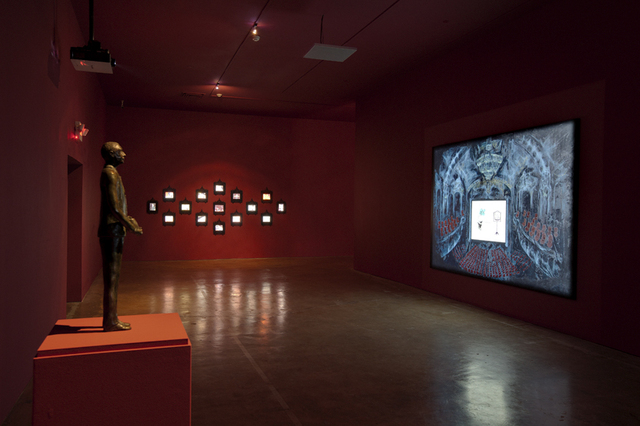

The Dissolve Runs through Jan. 2 SITE Santa Fe1606 Paseo de Peralta, Santa Fesitesantafe.org