“I have never let my schooling interfere with my education,” the famously erudite Mark Twain once said. Amherst graduate Calvin Coolidge agreed. To him, nothing was more important than persistence. “The world is full of educated derelicts,” he quipped.

Try and tell this to someone like Arnold Hitler, though. To the hero of Marc Estrin’s earnest second novel, education (as in academe) is his ticket out of his hard-luck Texas background. Saddled with an unfortunate name and an ignoble family line, Arnold needs every bit of help he can get in climbing life’s ladder. The first rung up for him is entrance to Harvard.

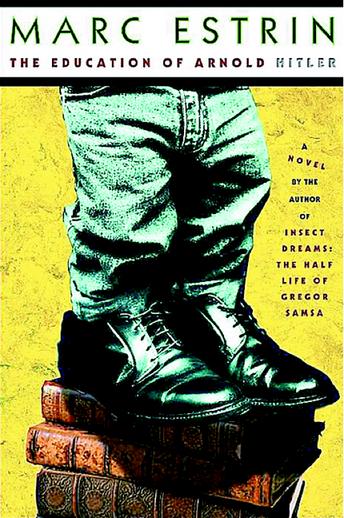

And so we wind up with The Education of Arnold Hitler, a novel that pits man’s inhumanity to man against higher learning. It will not spoil a thing for me to reveal here that education—in the U.S. News and World Report College Issue sense of the word—takes a bit of a beating.

The novel’s first scene describes Arnold’s first memory, which is of watching a lynching unfold in Texas in 1956. Rather than run home, Arnold’s father raises his son high above the crowd so he can drink in the spectacle. This is how life really is, the gesture says.

Arnold’s father knows a thing or two about mankind’s baser instincts. In a fit of John Irving-like plotting, the book flashes back to reveal that Mr. Hitler met Mrs. Hitler in Germany, where he was an American G.I. and she was an Italian he accidentally paralyzed with his hand grenade.

Somehow this explosive beginning leads to a marriage and from there to America, where Arnold comes into the world, kicking and screaming. He later gains the ability to talk to his long-dead grandfather through his knee.

These whimsical flourishes suggest The Education of Arnold Hitler might become an unpredictable book, a quirky one. It’s not. The deeper one reads into it, the more it resembles Winston Groom’s novel, Forrest Gump, which chug-chugged its hero through several decades of American history.

Estrin’s previous novel, the oddball picaresque Insect Dreams, also displayed a documentary urge, but it was a more creative enterprise. The lead character of that book was none other than Kafka’s infamous man-bug, Gregor Samsa, and the going got thick when Samsa joined a carnival freak show. He later went on to be a witness at the Scopes trial and joined up with the Manhattan project.

Reading The Education of Arnold Hitler, you get the sense that Estrin is more interested in documenting the latter half of the 20th century than he is the felicities and failures of his character’s life. This is a shame, since the novel’s opening promises a quirky and engaging character, a kind of cousin to Brady Udall’s inspired hero, Edgar Mint, who began his life story, The Miracle Life of Edgar Mint, with this sentence: “If I could tell you only one thing about my life it would be this: when I was seven years old the mailman ran over my head.”

Unlike Mint, who is remarkable for the sturdiness of his skull, Arnold becomes interesting because of what he can cram inside his own. He reads and he writes, asks questions and sees films. “The Seventh Seal was something else entirely,” Estrin writes in a typical passage. “It unveiled a whole new way of seizing the world, the way of images that spoke more than they said.” The description goes on for another paragraph or so before it melts back into Arnold’s life.

It would be unfair to fault Estrin here for wanting to paint Arnold’s childhood with shades of media and culture. They are our filters, in many cases, and they were Arnold’s, too, but a novel cannot simply describe an education—the classes one takes, the movies one sees—and hope for us to care for its benefactor.

A curriculum is just a list of tasks; it’s what it builds on the inside that counts and beguiles. It’s a mysterious process, but one that remains just as murky after we finish Marc Estrin’s second novel. Perhaps it will be clearer in the next one.