Why is it, then, that so many men freak out about losing their hair? Why is baldness so loathed or mythologized?

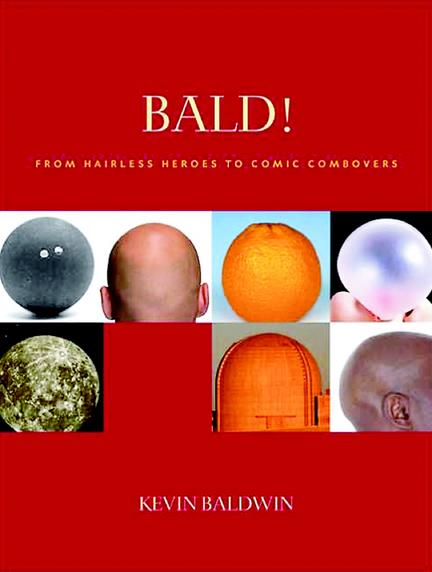

Kevin Baldwin (yes, that is his real name), having gone bald himself, has thoroughly researched the subject and produced a remarkably smart book, appropriately titled Bald. Who would have thought that 200 pages of bald trivia would be so interesting?

With his British wit and charm, Baldwin covers everything about baldness (no pun intended), from its supposed causes to purported cures. He documents jokes and quotes, song lyrics and random tidbits, along with old-tyme advertisements for baldness remedies. He lists derogatory nicknames for bald men, as well as for toupee wearers. He lists famous bald men, and a few women, too.

Perhaps the best list is of common and literary references to things that resemble a bald head: for example, “his head as bald as a bladder of lard,” from Robert Louis Stevenson's St. Ives. He lists both positive and negative traits that have historically been ascribed to bald men, juxtaposing inconsistent stereotypes to illustrate the silliness of them. For example, baldness has been deemed both a sign of virility and a sign of sexual suppression.

One chapter tells the history of the world through an accounting of bald leaders. Among the men listed are the Roman emperor Caligula who “whenever he came across any good-looking men with a fine head of hair, he disfigured them by having the backs of their heads shaved.” In 843 A.D., “Charles the Bald became King of France. It may not sound like the most flattering epithet, but it could have been worse. Charles the Fat became Holy Roman Emperor in 877, and Charles the Simple became King of France in 893. Charles the Bad was King of Navarre from 1349, and Charles the Mad reigned in France from 1380 to 1422, despite losing his royal marbles in 1392.” The author also quotes Shakespeare (another bald man) on the two practical benefits of baldness: “The one, to save the money that he spends in [hair-dressing]. The other, that at dinner [his hairs] should not drop into his porridge.”

Among the 10 disadvantages of baldness, Baldwin lists the fact that “it takes longer to wash your face, since there is more of it—and if you have your face painted when attending a football match, it will cost you twice as much as a person with hair.” But there are 40 “advantages of alopecia,” including the fact that without hair you cannot get lice or get bats caught in your hair; and, of course, “you can never have a bad hair day if you don't have any.”

In the end, Bald is a bit of love for the men who might otherwise feel marginalized in the “sexiness” polls, notwithstanding the actors named above. The book favorably references great bald men and portrays baldness as both natural and attractive. It also laments the ongoing discrimination against the follicularly challenged.

“It is no longer acceptable to laugh at people because of their colour, sexual orientation, height or weight, but for some reason the PC police have not clamped down on anti-hairless humour,” the author laments. But Baldwin also provides a chapter on clever comebacks for bald men who are subject to such thoughtless mockery, including “at least I'm only deficient on the outside of my head,” and “they don't put marble tops on cheap furniture.”