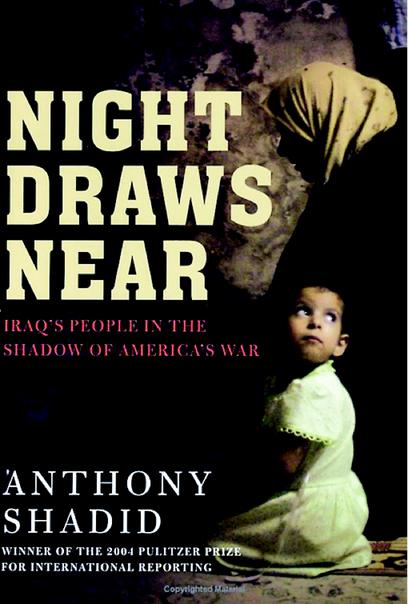

In Night Draws Near, Anthony Shadid corrects this hideous oversight with a powerful glimpse at the effect this war has had on everyday Iraqi people. It is a beautifully reported, crucial piece of context in a war where, as it turns out, context was everything.

“Time and again, I am struck by how seldom I hear the word, hurriya, ‘freedom,’ in conversations about politics in the Arab World,” writes Shadid in his introduction. “Much more common among Arabs is the word, adil, ‘justice.'”

This book captures why Iraqis feel their sense of justice has been trampled. For starters, as he reminds readers, the country the United States invaded had been suffering through wars for more than 30 years. The most costly of these conflicts was the Iran-Iraq War, started by Saddam Hussein, but funded largely by the United States. More than a quarter million Iraqis died in that conflict alone.

Roaming the country, Shadid talks to men forced into duty for that war, some who spent a great deal of it in Iranian prisons. One of them recalls Iraqi soldiers so desperate to get home they’d step on land mines, in hopes the explosion would take just a part of their body.

It’s easy to see why these veterans would want never to go to war again. But, of course, they did.

Shadid didn’t speak only to former soldiers. Born in Oklahoma of Lebanese heritage, he was one of the few Arab-American writers in the Middle East who spoke Arabic, and he used his understanding of the culture to gain access to the thoughts of everyday Iraqis.

He talks to newly trained police forces in the Sunni Triangle, to intellectuals, to average men and women who waited out the “shock and awe” campaign in their homes, blasts coming so powerful they ripped open the doors of refrigerators and shattered windows. One man explains why Iraqis who hated Saddam hate the invasion even more: “What gives them the right to change something that’s not theirs in the first place? I don’t like your house, so I’m going to bomb it and you can rebuild it again the way I want it, with your money? I feel like it’s an insult, really. What they’re doing to us, they deserve to have done to them … their children.”

The complaints heard so often in the news—the lack of security, clean water, electricity—are repeated here, but when attached to people they mean something tangible. It seems obvious that, left unsolved long enough, such legitimate complaints would coalesce around a leader who arose from the street, such as Shiite Muslim leader Moqtada Sadr, whom Shadid interviews when he is thrown into the limelight, awkward and blinking, a figure of resistance.

Shadid believes the confrontation between Sadr’s army and U.S. forces in Sadr City last August was inevitable. It came as the result, he says, of misinterpretations and a lack of sympathy. And it was kicked off in part by the image of a U.S. helicopter trying to knock down a flag inscribed with the name of an important religious figure. Broadcast over Iraqi TV, the picture infuriated Iraqis already on edge.

Perhaps it looks different within the fog of war, but from hindsight, it seems impossible not to interpret these events as precursors to a nationwide insurgency, led, Shadid makes clear, not from one source but from a variety of people united by a language of religion.

“Iraq had now joined Palestine and Afghanistan, Chechnya and Bosnia, all countries where a besieged Muslim population was pitted against a more powerful foe,” he writes. When Night Falls reveals that this war might have gone a different way if we had listened to the people of Iraq as Shadid did from the beginning.