Billed as a zeitgeist-grabbing inner-city drama with its roots in the proto-gangsta sagas of the early '90s (Boyz n the Hood, Menace II Society, Juice and South Central forming the central axis of said movement), ATL actually hearkens back to the formative years of Hollywood's “Cinema of the Other,” when nascent agent provocateurs like Melvin van Peebles were annealing the metal-edged cusp of the early Blaxploitation genre with their white-hot outbursts of darkly comic invective. It was films like Boyz n the Hood, with their emphasis on post-Italian neorealism, that led directly to the more hyperbolic (some might say “hyper-real”) depiction of today's street culture as reflected in the controversial lyrics of rap performers like Eminem and 50 Cent. (There are those who would also argue that the postwar dissatisfaction and economic hardship that led to the formation of the Italian neorealist movement are the very forces that are providing the Sturm und Drang in today's inner city, making the gritty realism and emotional verity of Vittorio De Sica's 1948 masterwork The Bicycle Thieves a thematic progenitor to the situational ethics of the Hughes brothers' watershed 1993 hood drama Menace II Society–of course, such speculation brushes aside the more brusque qualities of neorealism, a naïve regime with a mistrust of oversentimentalization and only cursory gestures of working-class solidarity, making it ultimately far less rewarding than the later cinema verité movement with its greater emphasis on empathy of character.)

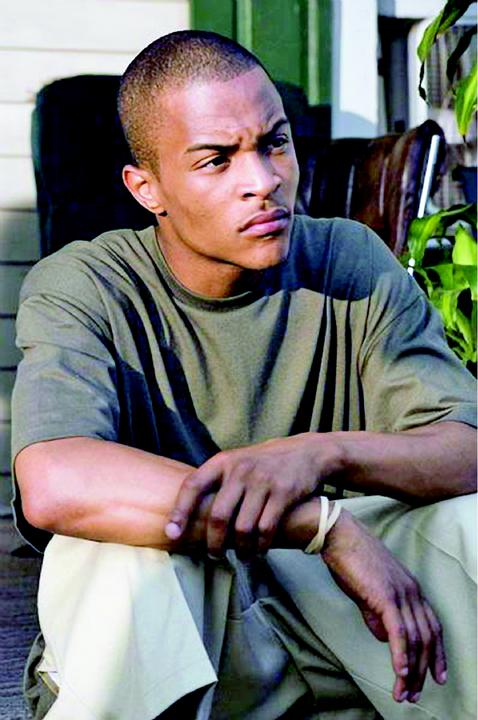

Slightly less interested in the machismo-fueled money-mongering of the gangsta sagas, ATL instead casts its concerns on the day-to-day lives of four best friends on the verge of graduating high school. Our Dante-like narrator on this inner-city journey is Rashad (Tip Harris, a professional rap star whose nom de rue is T.I.). Rashad is a typical screenwriter substitute–in this case a comic book artist–whose dreams of escape from all-too-humble roots provide the film with its dramatic crux. Rashad's parents are deceased, but our protagonist finds a certain raison d'etre in the guardianship of his younger brother Ant (Evan Ross) and in the camaraderie of his best friends Teddy (Jason Weaver), Esquire (Jackie Long) and Brooklyn (Albert Daniels), all of whom are formulating their matriculatory plans.

Drama (and a good deal of humor) centers around the social hub of the teens' Atlanta neighborhood, a roller-skating facility where adolescent bragging rights are established by an elaborate courting dance in which class boundaries are subservient to performing skills. Like John Travolta's disco club in Saturday Night Fever, this terpsichorean facility serves as an escape from the harsher realities of metropolitan existence–although, coming as it does in the wake of the mise-en-scene similarity of 2005's skate-centric dramedy Roll Bounce, the film can't help but feel emulative.

Over the course of the temporally brief narrative, the boys are confronted with several obstacles, some of which serve as challenges to their esprit de corps. Rashad woos a young lady (a “hottie” or “shorty” in the parlance of the region) and tries to prevent his younger brother from succumbing to the economic siren song of the drug industry. Esquire, seeking entrance to an Ivy League university, cozies up to an African-American business leader (Keith David, one of the few full-time actors employed in the cast). Others are around primarily for comic relief. Eventually, the film's storylines coalesce, bringing various disparate characters together for a dramatic dénouement that confirms the film's more humanitarian outlook.

By employing a cast of mostly unknowns and unprofessionals, first-time director Chris Robinson aligns himself with historical filmmakers like Herbet J. Biberman, one of the Hollywood Ten, of course, whose subversive 1954 feature Salt of the Earth famously utilized non-actors (a trend echoed by Steven Soderbergh's recent experiment Bubble, which eschewed professional acting talent, availing itself instead of numerous real faces from the town in which it was filmed). By employing respected Atlanta-based rappers like T.I., Jazze Pha and Outkast's Big Boi, Robinson formulates a milieu that both fulfills the idol-worshipping needs of today's youth and captures a truism that rap stars are the most significant dictators of taste and style in modern American society. (See also: 8 Mile, Get Rich or Die Tryin'.)

With Three 6 Mafia winning Academy Award accolades for their work on the rap drama Hustle & Flow, it seems as if the mainstream flow of Hollywood has finally merged with the increasingly hydrodynamic output of our country's African-American culture. ATL–with its engaging cast, imponderous attitude and refreshingly colorblind outlook on social struggles (putting forth the conceit that economy and upbringing are more significant factors to ascendency than skin color)–“keeps it real,” establishing itself as a successful work of art, offering harmonious parity between teen-based Saturday night divertissement and representational depiction of regnant urban culture as filtered through the eyes and ears of modern-era hip-hop.