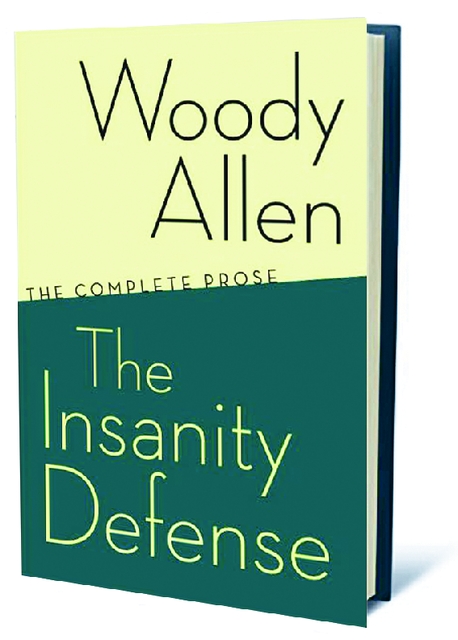

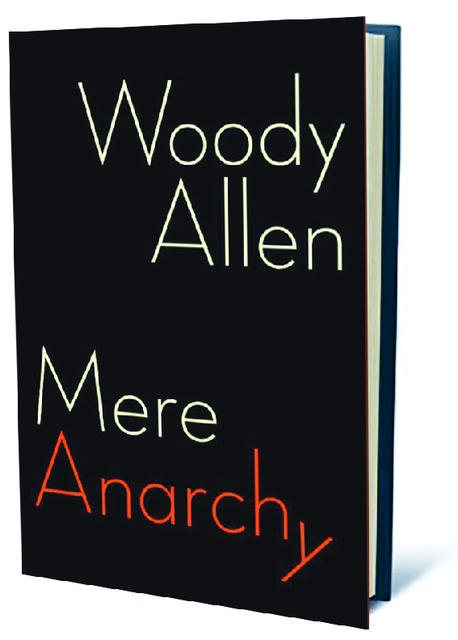

Somewhat Hilarious

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992