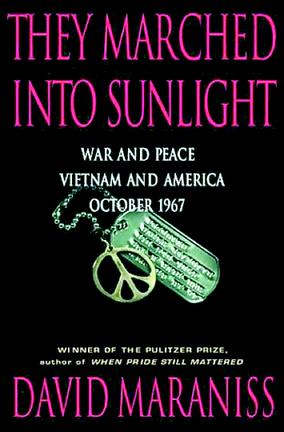

In They Marched into Sunlight, David Maraniss fashions an empathetic group portrait: students, faculty, administrators and campus cops at the University of Wisconsin, and a battalion of soldiers in Vietnam, as their lives unfolded, and in some cases ended, during the month of October 1967. Maraniss focuses on two events: a student protest against the UW practice of inviting Dow Chemical recruiters (Dow manufactured napalm and agent orange) to hold on-campus job interviews and, during the same month in Vietnam, the ambush of three companies from the famed Black Lions battalion while on a search-and-destroy mission in which over 60 Americans, including two renowned officers, were killed. Both the protest, which turned violent, and the ambush, are emblematic of what would occur across U.S. campuses and in Vietnam for years to come.

Eschewing discussions of policy and ideology, Maraniss constructs a detailed narrative of individual action and motivation, cross cutting from scenes of student meetings, sit-ins and anxious administrative huddles to nervous recruits and their gung ho commanders as they endure the rituals of modern war and trudge blindly into the horrific test of battle. Everyone from the humblest foot soldier to the most ardent self-fashioned radical to the chancellor of the university struggles to find a balance between his or her moral conscience and a sense of duty, between fear and faith in tradition and law.

Like a good novelist Maraniss lets his larger theme emerge suggestively out of the human details. What Vietnam comes to signify is not a failure of people but of institutions: the army, the university, the corporate community, the transparency of democratic government. One of the book's most telling stories is about supplying soldiers with food.

To keep the jittery grunts happy, the U.S. Army constructed 40 ice cream factories in South Vietnam. In contrast, a typical Viet Cong supply line consisted of a single man transporting hundreds of pounds of rice on a bicycle lurching down rutted jungle paths. As a Viet Cong doctor put it, it was “like Robinson Crusoe on the island.” While the U.S. dished out false body counts and homey sweets in the midst of a bloody fiasco, the Viet Cong imagined themselves the inheritors of the Protestant work ethic, a moral touchstone of liberal capitalism.

Near the end of the book Dick Cheney, then a graduate student at UW, makes a cameo appearance, stepping blithely past the protestors on his way to class. For Cheney, the days of rage were nothing but “a minor hassle.” The VP had a point. While radicals romped in Madison, Berkeley and Chicago, Cheney and his ilk hunkered down to hardball politics. But Republicans and leftists agreed: “Liberal” was a dirty word.