Ouch! I can't tell you how that pains me. As a professional book reviewer, I'm really beginning to feel the gouge of my impending obsolescence.

I console myself with a couple cheering thoughts. For one, we don't have data yet for 2004, so maybe we, as a nation, are already in the process of reversing this alarming trend. Second, if you base your judgment purely on the truckloads of political books that are presently getting dissected and regurgitated in almost every nook and cranny of our national culture, you could easily get the impression that Americans are gobbling down books with the same relish and speed they usually reserve for Krispy Kremes.

Now, that's a delusion I don't mind embracing.

Of course, most of the political books hopping around the top of the bestseller lists this year are hysterical, sweaty, red-faced attacks of one kind or another. These books mostly seem designed to land blows in the bloody battle over control of the White House and Congress. The authors are obviously sincere in their political beliefs, but their rants are meant to polarize. They write with such passion because they're eager to do their part to affect the outcome on Nov. 2.

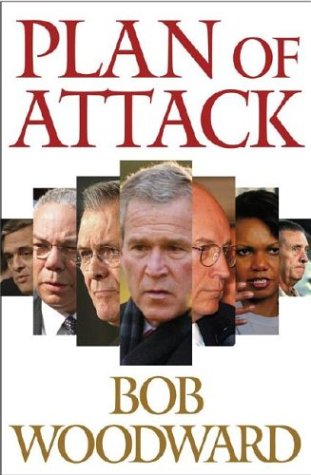

Thankfully, Woodward's latest is one of the least partisan political tomes of the season. We expect nothing less from the Washington Post editor who, with Carl Bernstein, revealed the depths of Nixon's crookery. Woodward is, after all, a real honest-to-Jesus journalist, which apparently still means something in obscure, outback corners of the globe. As far as I can tell from Plan of Attack, Woodward doesn't seem to give a damn whether or not his book will affect the attitudes of potential voters. He's simply interested in communicating the truth. What a novelty.

Not that political operatives in both major parties aren't shooting out information found in Plan of Attack as election year ammo. They are. And Woodward has unwittingly supplied bullets to both camps.

You'll recall that Woodward's 2002 book, Bush at War, discussed President Bush's response to 9-11, focusing primarily on the war in Afghanistan. The book painted Bush in a strikingly … ahem … positive light. Republicans waved that thing around for months afterward, gloating that one of the world's most respected journalists had produced a book that proved their man in the White House was a smart, confident, tough leader in a time of crisis.

The success of Bush at War apparently made Bush eager for a sequel. According to Plan of Attack, the president actually suggested that Woodward write one with the subject being the 16 months leading up to the war in Iraq. Woodward promptly took him up on the offer.

The president gave the journalist unprecedented access to the inner workings of an administration that's undoubtedly one of the most secretive of modern times. Woodward interviewed the president on the record for several hours. He also did extensive interviews with 75 other key players off the record.

The results are amazing. Woodward delivers a scintillating, one-of-a-kind account of what went on behind the scenes as the administration wrestled with the question of Iraq. In the process, he also tells some highly readable stories about top secret intelligence operations that set the stage for the war.

Right-wingers will find plenty here to support their glowing view of the Bush administration. One of the best things about the book is that Plan of Attack gives readers an insight into the main personalities—Rumsfeld, Cheney, Rice, Wolfowitz, Powell, the president himself—and how they behave once the television cameras are turned off. Contrary to left-wing caricatures, most of the members of the Bush administration, including Bush himself, come off as thoughtful people genuinely concerned with doing what they can to secure our nation. This is always their main worry, even above and beyond the obvious financial benefits that come with invading a country with the second-largest established oil reserves in the world.

The president in particular seems more alert and probing than might be expected, although he certainly isn't detail-oriented—to put it lightly—and he seems to have a deep psychological fear that others won't perceive him as a manly man of action. Even so, if Plan of Attack is to be believed, it's definitely Bush, and not Cheney, who calls the shots behind the scenes at the White House.

As many reviewers have noted, however, Plan of Attack is a much less convincing vehicle for the glorification of George W. Bush than Woodward's previous book, Bush at War. For one thing, the book reveals that the administration was formulating plans to invade Iraq long before they publicly admitted to it. When President Bush, for example, claimed in the media that he didn't have any plans for attacking Iraq “on my desk,” he may have technically been telling the truth, but in a practical sense, he was lying through his teeth. The plans weren't physically on his desk (the president apparently keeps a very clean desk), but Gen. Tommy Franks had already created updated war plans for Iraq at the president's request.

The truth is that key members of the Bush administration, especially Cheney, had been fixated on invading Iraq long before the catastrophe of 9-11. According to Woodward, Secretary of State Colin Powell believed Cheney “was beyond hell-bent for action against Saddam.” Other key players, notably Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz, were in the grip of the same kind of fever.

From my own admittedly biased, liberal perspective, Woodward's book has made me more convinced than ever that the administration's extremist right-wing world view—which, among other quirks, consists of the belief that God always sides with the United States—deluded them into believing going to war with Iraq in the manner they chose was a good idea. Plan of Attack reveals that there were plenty of voices within the intelligence community expressing skepticism over the administration's repeated public assurances that Saddam possessed vast quantities of weapons of mass destruction. Bush and company simply opted not to listen to them.

Powell, one of the few high-level Bush administration officials with any significant military experience, was the most reluctant major player. Even he, though, eventually fell into line. As Woodward makes clear, when Powell gave his presentation to the United Nations in early 2003, the Secretary of State placed all his evidence in the most negative light, leaving not an inch of room for nuance. As a result, the world got a false—or, at best, strikingly incomplete—impression of the probable dangers posed by the Iraqi regime.

Unlike a lot of liberals, I don't believe Bush is stupid. I do, however, believe that he's both arrogant and dangerously narrow-minded.

The most interesting part of Plan of Attack is the lengthy epilogue in which Woodward interviews the key players about their current impressions. At one point, the famous journalist mentions to the president a conversation Woodward had with Tony Blair. The British Prime Minister recalled receiving venomous letters from mothers who said they hated him for sending their sons to their deaths in a pointless war. Blair told Woodward, “Don't believe anyone who tells you when they receive letters like that they don't suffer any doubt.”

When Woodward related this story to Bush, the president said smugly, “I haven't suffered doubt.” I don't know about you, but that statement scares the crap out of me.