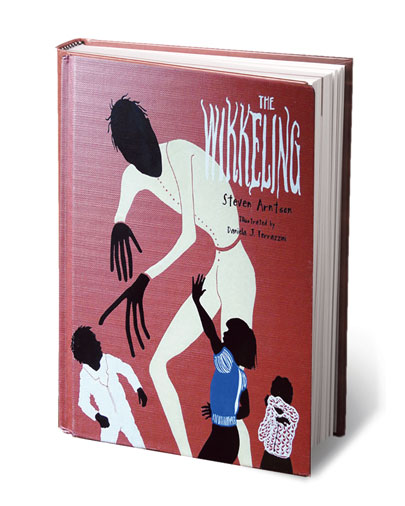

Interview: Steven Arntson, Author Of The Wikkeling, Visits Albuquerque

Kids’ Novel Is Engaging And Spooky For Adults, Too

Steven Arntson

Heather Mathews

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992

Steven Arntson

Heather Mathews