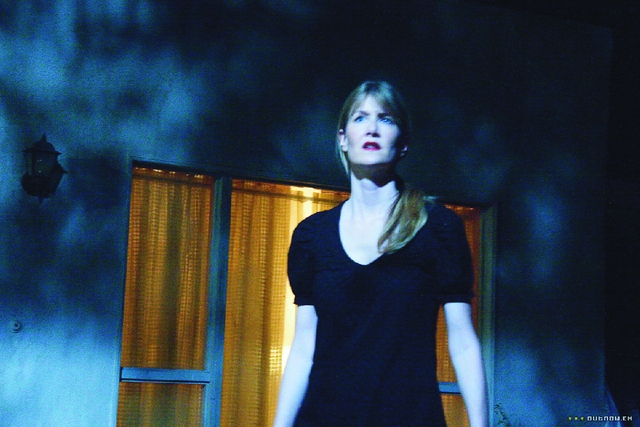

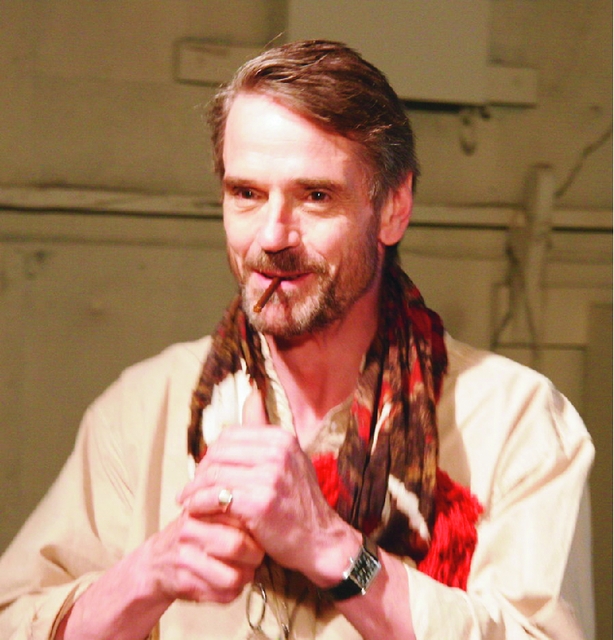

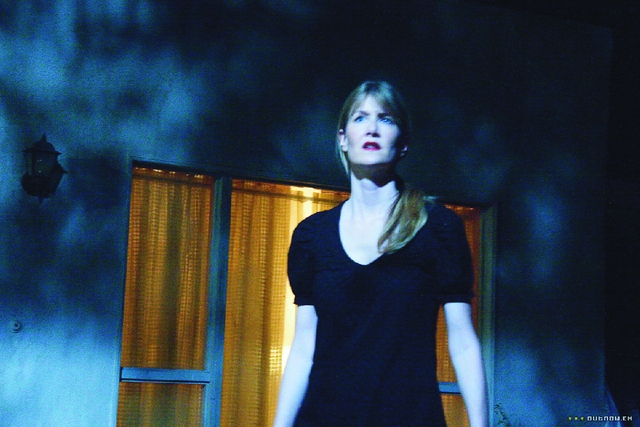

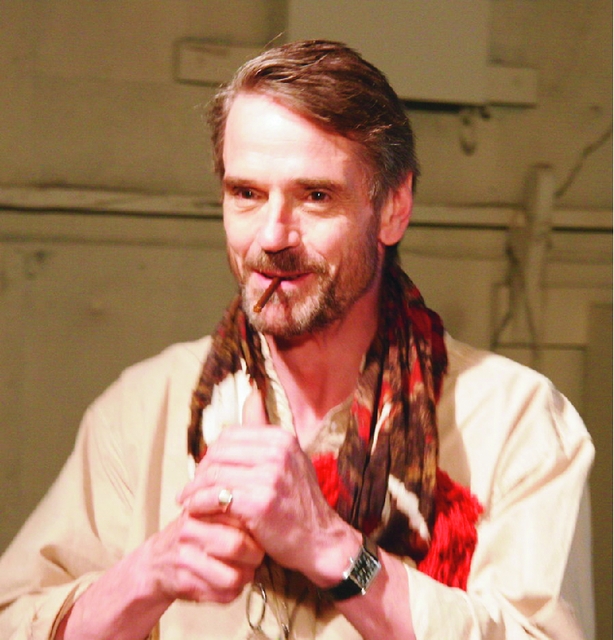

Inland Empire

Lynch Goes Epic For Some Shot-On-Video Strangeness

“I have no idea what’s going on

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992

“I have no idea what’s going on