Every morning, whether it was freezing or raining or windy, in the most inclement weather, reluctant or otherwise, I rose with the sun and went jogging along the river … I aligned my feelings to appreciate the birds, water, air, noting the subtle significance of colors and textures around me from the tiniest grass tendrils and buds to the birth of mallard ducklings wiggling behind their waddling mother inla acequia.— From the Author’s Note in Singing at the GatesThis passage and the physicality of so many of his poems resonated with me. I asked Baca how the running that he mentions so often has informed his writing. “Running, or any exercise,” he began, “is essential to a healthy lifestyle, and to art.” I was a little disappointed with his prescriptive response, but then he continued on with the vehemence and conviction that expresses itself in every line of his poetry. “Most artists are trustfunders and ass-kissers. The hardcore artists who are born into families with working mothers and fathers gone and [who] have to earn their living know the beauty of a cheap man’s joy—that is, running, and we revel in it … revel.”

I want Justice afoot in each house,whether parquet floor or mud floor. I do not want its sweet face,its drop of blood pinched form a pimple,or a cherry in a gentleman’s evening drink itspride.— From “With my Massive Soul I Open”Of the nearly seven years that Baca spent in maximum security prison, three of them were in isolation. The reality of life as an inmate, as he writes in “What’s Happening”—“ … the weeping, and the hate, and the blood!/ And the despair, and the rehabilitation!” is a parody of reformation. Baca snidely includes “rehabilitation” in his poem on the heels of blood and despair. Growing up an orphan and later a runaway, and an Indio-Mexican one at that, Baca saw no reflection of himself in society, or at least not a peaceful one. There is such vitriol in some of Baca’s poetry that reflects the injustice of racism, economic disparity and the sometimes turbulent experience of growing up in the Southwest’s barrios. I asked Baca if he was still angry. He answered simply, “I hope so.”“What are you angry about? What is there to fight against?” I asked him and with his poet’s elegance and honest, virulent way of speaking his truth he answered, “We live in a war economy, our politicians are greed-incensed monsters with brains the size of a flea’s testicle, our judges are commodities to buy and sell, our police are marauding vigilantes, our bankers and stock brokers are nefarious criminals who rob the weakest in our communities, our schools are smash ‘n grab mosh pits where politicians steal as much money as they can and abandon the children to their own penury, in short—our society has bottomed out so people who have given up all hope [resort to] consuming pharmaceutical drugs to numb themselves to their own madness.”Categorically, he added, “[I] don’t give a shit about rich people and in fact, I despise them. I started a line of toilet paper with [Donald] Trump’s face on every square and wipe my ass with his face.”

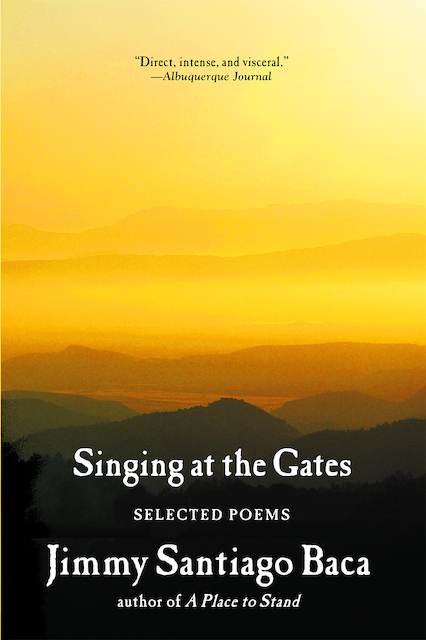

I praise short lives, and believetheir souls blend into the grayRio Grande, coursing between broad,hefty cottonwoods that crowd the banks,emptying into the ocean,where I hear them whisper—From “It’s an Easy Morning”I make a point of seeing the river most days. I thought a lot about it while reading Singing at the Gates. From the West Mesa to Downtown to the Foothills, the landscapes of New Mexico are recurrent, creating a texture and backdrop for the biography that develops over the course of the poems collected in Singing at the Gates.“The Rio Grande is a barometer of our sanity—if we honor it, we honor all peoples, if we don’t, we die,” Baca said of the great river that courses, sometimes slowly and shallowly, through Albuquerque. It is a dark ribbon winding throughout Baca’s poetry, which has particular resonance with people familiar with the topography of the Southwest. Here, there are poems about the strange, evocative landscapes of the desert—“In the Foothills” is about the Sandias, “Silver Water Tower” distinctly references Estancia, “Walking Down to Town and Back” is about traveling on foot to Belen.When asked about the relationship his writing has with the Southwest, with his particular brand of rough romanticism Baca answered, “We have an ongoing love affair. And in that sense, I’m a sex addict.”

It never ends. This harsh beauty,this struggle not to retreat in fearbut to celebrate what’s hard earned, staying trueto myself,is what it’s all about.—From “This Dark Side”These days, Baca holds workshops for those who are overcoming hardships—he visits prisons and underserved schools and works with his nonprofit, Cedar Tree, Inc., which empowers individuals through education. Baca manages to maintain the perspective, the raging sense of injustice and the conviction that made his poetry so great in its early years, but his work these days is also tempered with a sense of joy—in nature, in love, in the sweetness of life after coming through the darkness. Like the warrior poets of old, Baca is mighty and complex, just like his poetry.