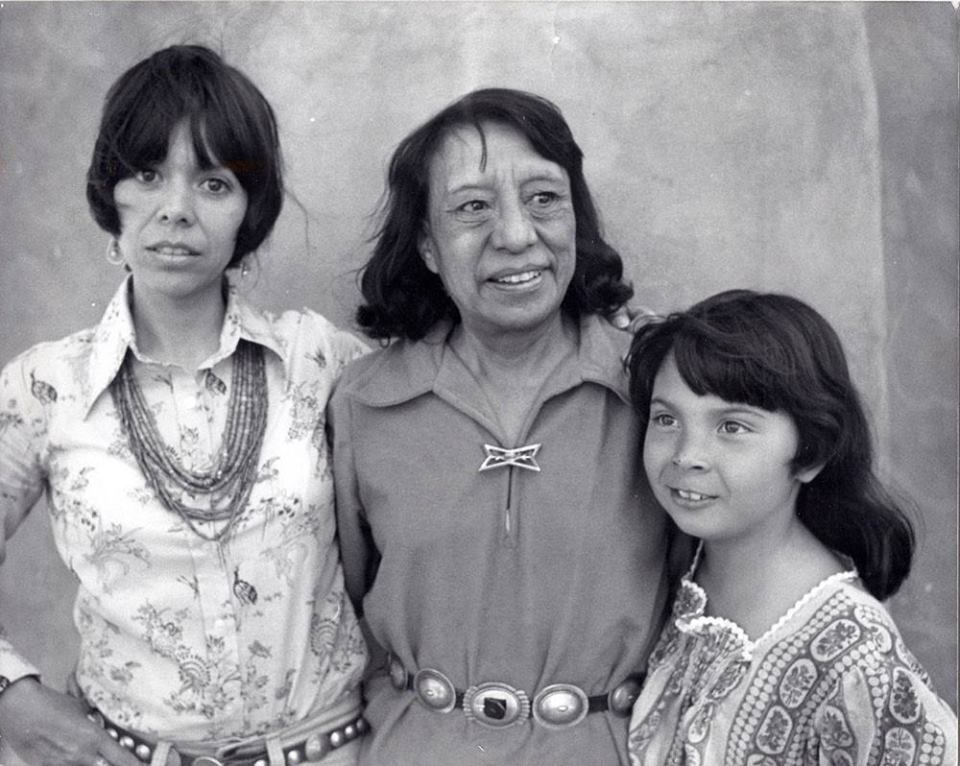

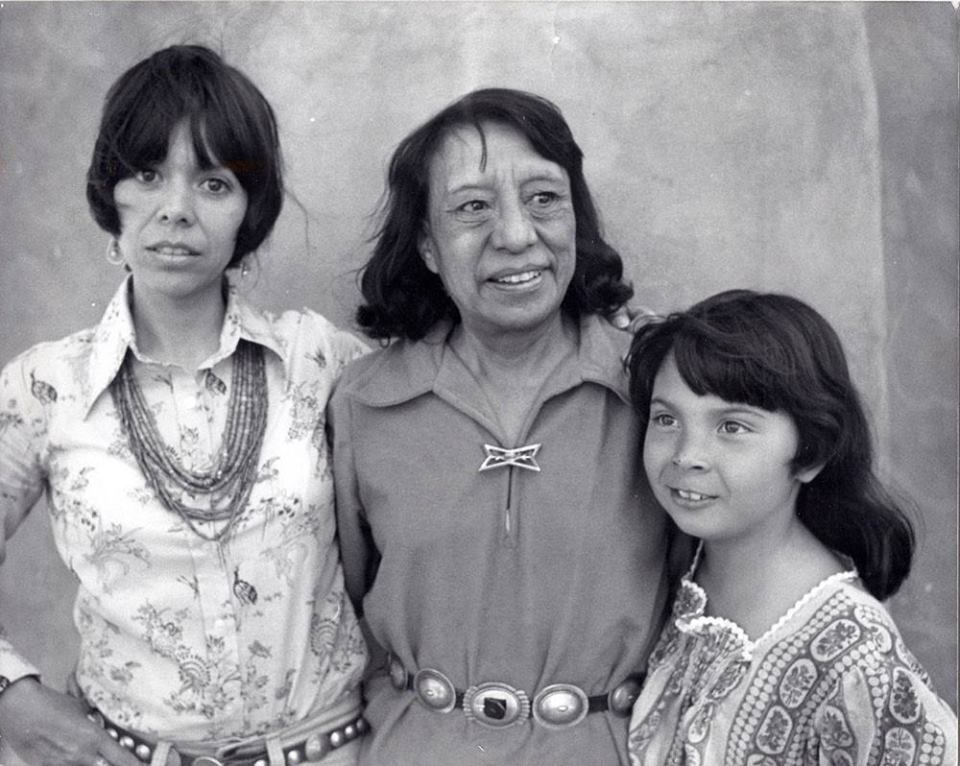

Culture Shock: Honoring Blood And Culture

The Artistic Legacy Of A Matriarchal Dynasty

IPCC

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992

IPCC