Culture Shock: The Country In Both Darkness & Light

Terry Tempest Williams’ The Hour Of Land

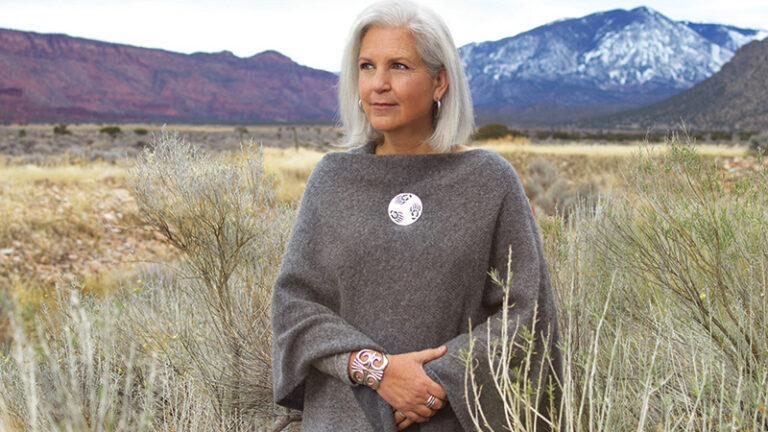

Kwahu Alston

Kwahu Alston