Culture Shock: Frida Kahlo Through The Lens

Her “Battlefield Of Suffering” Illumined In 241 Photos From Her Private Collection

Frida stomach down, 1946

by Nickolas Muray courtesy of Frida Kahlo Museum

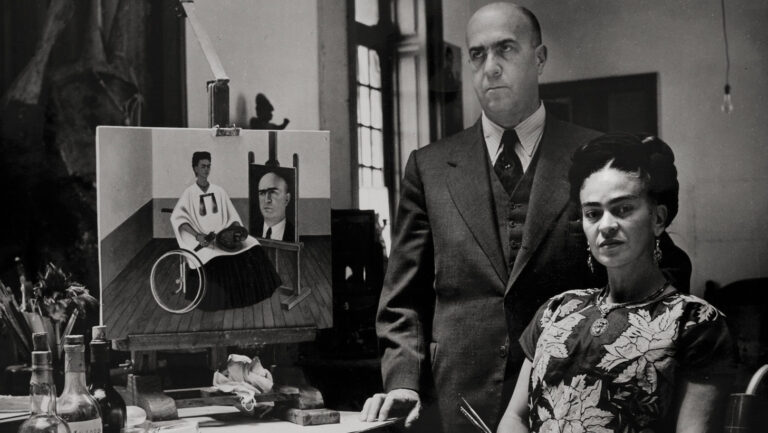

Frida Kahlo with the doctor Juan Farill, 1951

by Gisel̀e Freund courtesy of Frida Kahlo Museum

Frida Kahlo with the doctor Juan Farill, 1951

by Gisel̀e Freund courtesy of Frida Kahlo Museum

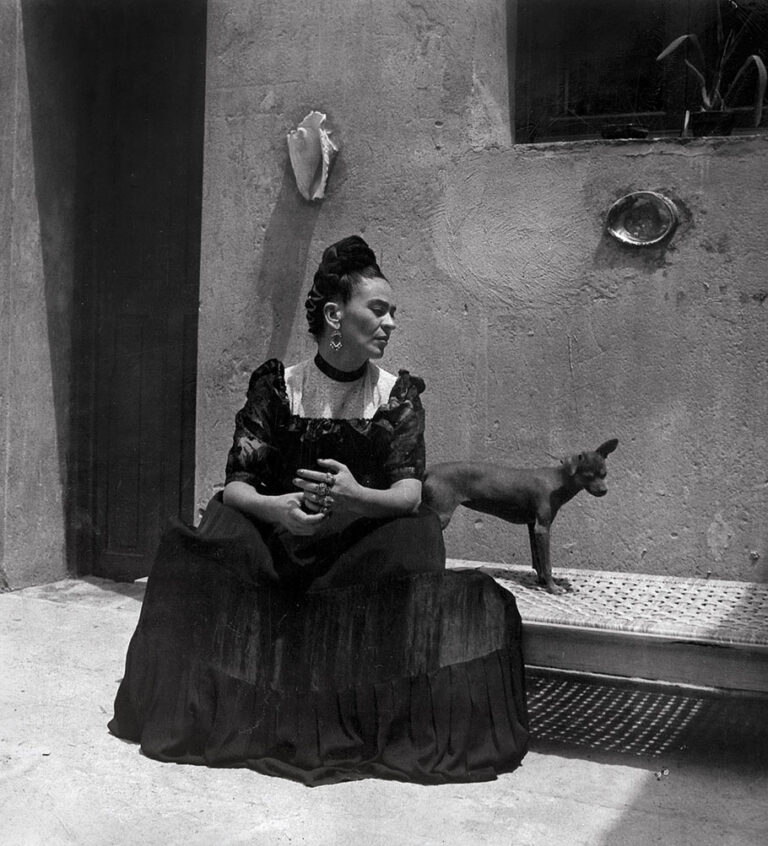

Frida Kahlo, ca. 1944

by Lola Alvarez Bravo courtesy of Frida Kahlo Museum