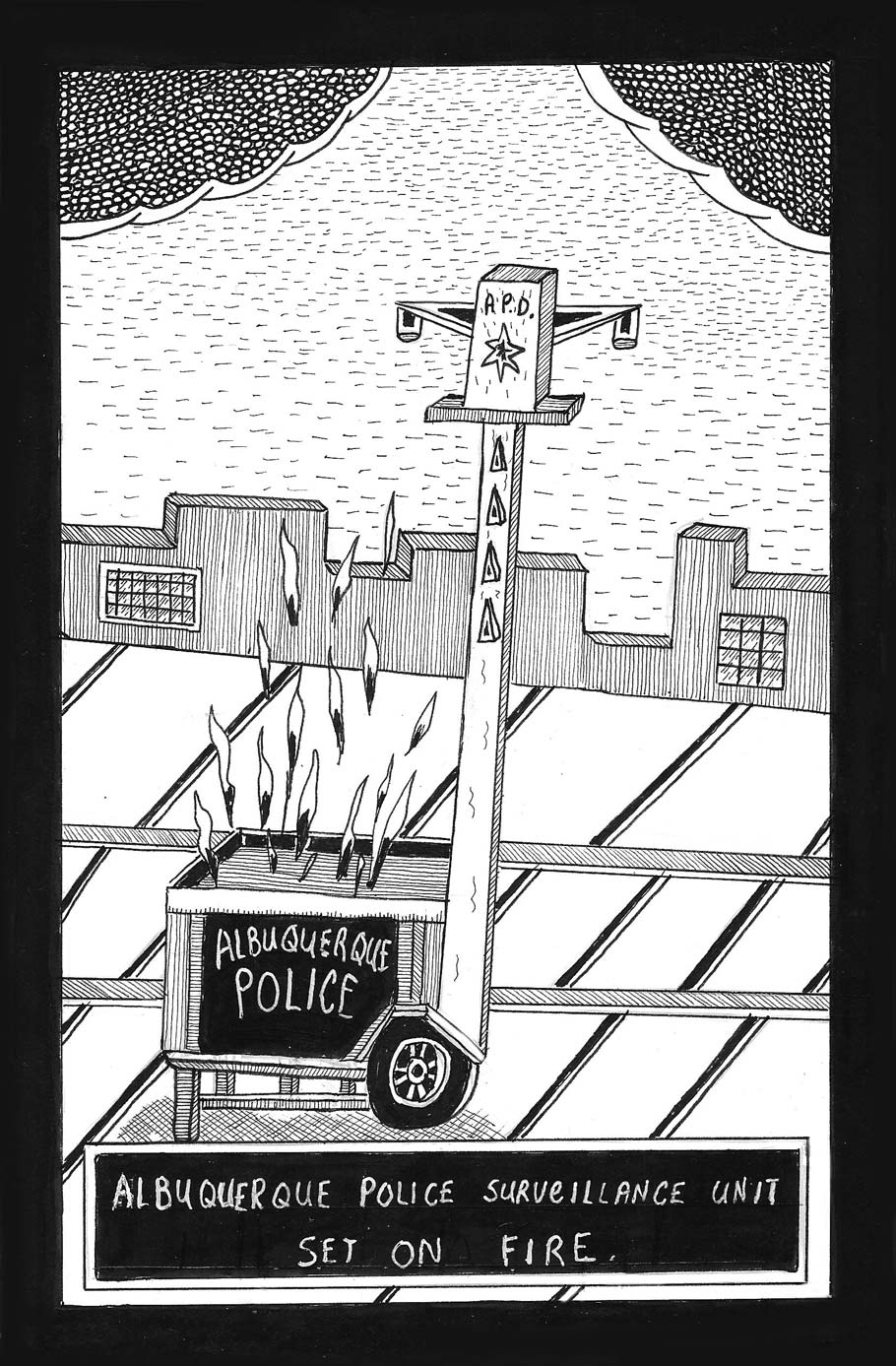

Culture Shock: Albuquerque Otherworld

Mark Beyer's First Collection In 12 Years Delves Into The City's Strangeness

Mark Beyer

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992

Mark Beyer