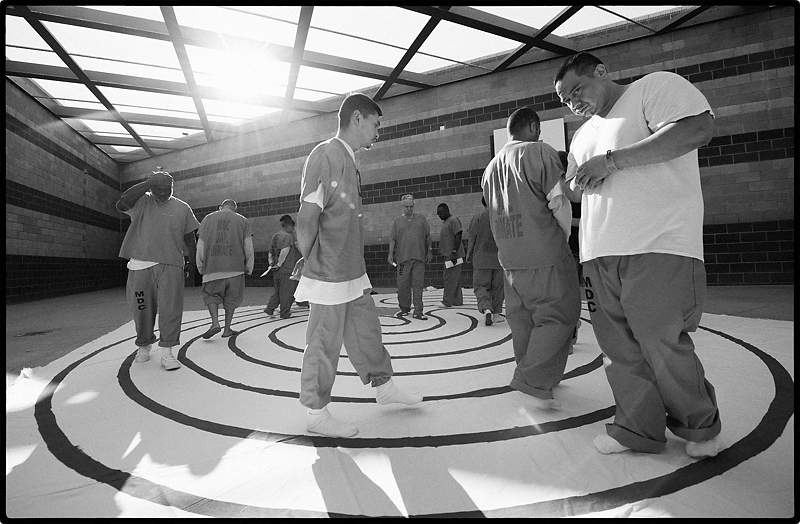

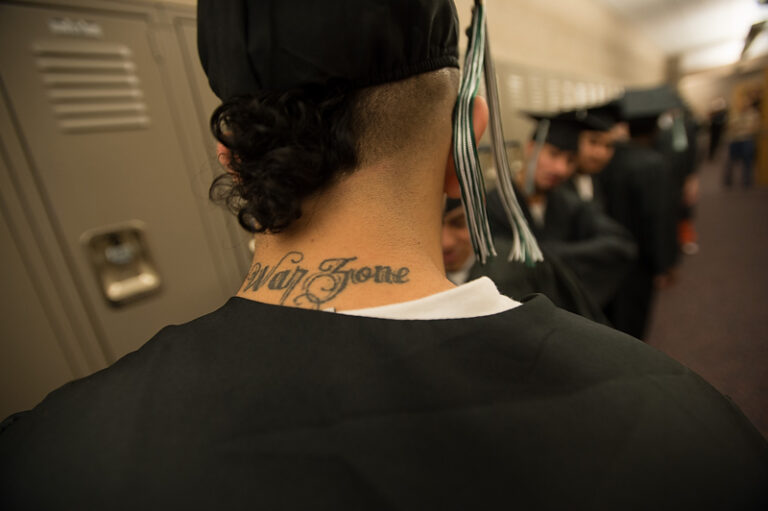

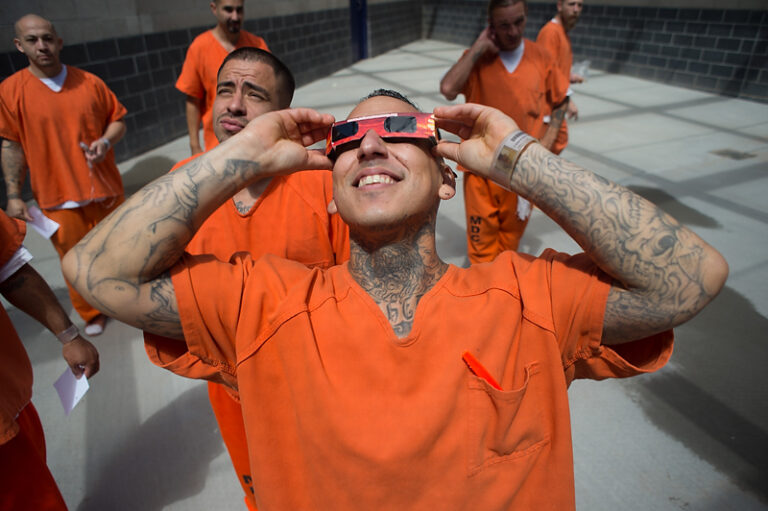

Culture Shock: The True Lens Of The Camera

Photographer Chris Cozzone Explores The Lives Playing Out In Albuquerque

Chris Cozzone

Chris Cozzone

Chris Cozzone

Chris Cozzone

Chris Cozzone

Chris Cozzone