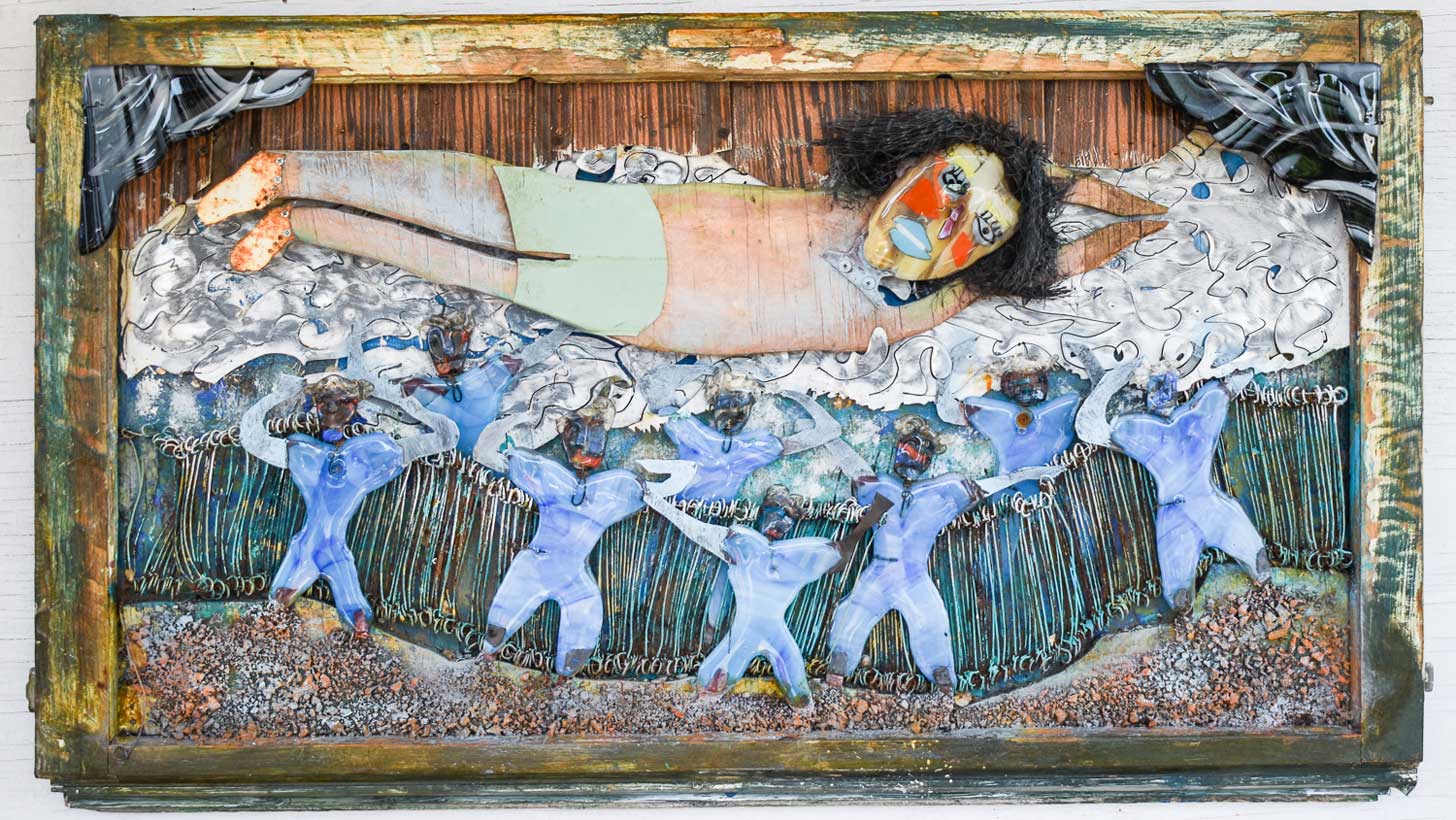

Mitch Berg is trying to inspire magic. He has been making art out of things he finds (glass, bits of metal, seed pods, etc.) for years, but is now trying to expand outward by bringing others into a collaborative art space that is as much physical as it is mythological. He wants to discover something through the process of taking on a challenge and there are few places filled with both myth and challenge quite like Albuquerque’s South Valley.When Berg moved down to the South Valley from Santa Fe, he had no idea what those challenges would be, just that he needed them. He started an art school. He dealt with the county. He began working with formally incarcerated men. He started piling stuff up in his yard with the faith that jumping into the unfamiliar was a transformative process whose benefits were real even if their parameters were incalculable.Weekly Alibi sat down with Mitch Berg among the crumbling adobe, repurposed shipping containers and reclaimed scrap metal of his South Valley compound for a conversation about what brought him there as he was readying a new exhibit of his work opening this Saturday in Madrid. The following is an edited version of that interview.Weekly Alibi: Where did you come from?Mitch Berg: From Wyoming. I have a degree in geophysics and editorial journalism and photojournalism [from the University of Wyoming]. I came to Santa Fe because I had met a girl. I had gotten a job in Denver at the Rocky Mountain News, but then my girlfriend at the time was like, “I’m not moving to Denver, I’m moving to Santa Fe.” So, I came down to Santa Fe. I did a freelance journalism thing with a glass artist named Duane Dahl. I started making these little tiny figures that I was selling at the flea market up in Santa Fe and I got the bug. People liked them and I was making a living. I applied to an art show in Berkeley, California because everyone who was buying my stuff were people that knew me like mom’s friends. You can’t really trust that. So, I decided I needed to do an art show that was far away. I did the show in Berkeley, California and sold everything I brought. I started collecting junk and using that with the glass work. I wasn’t quite sure what I was doing. I liked glass, but it’s kind of boring all by itself.When you went to Berkeley, did you bill yourself as a New Mexican artist?Oh yeah. That was a big deal. Honestly, every single time, even today, when you tell people that you are a Santa Fe artist their eyes just – “Oh, Santa Fe!”That is part of the myth of Santa Fe.It is. It just infused me with some magic quality. I was a Santa Fe artist. Never had an art class in my life.Outside of the mythology of Santa Fe itself, what role does mythology play in your work?I was a journalist and I just started writing about my own experience. I had been struggling with this idea of coming up with these mythological stories about who I am, how I got influenced, how we become who we become, what are the incidences – all of a sudden you are going along and something happens and you’re a different person on the other end.Turning points?Absolutely. But even more so. Rather than a turning point, for me it was always a challenge helping me discover who I was.What are those experiences called?I call my school Fuego because you need a spark. There is something that we all have inside of us. I think we live in the most limited version of ourselves. When we discover acts like – “Oh my god there is a child under that car” and you lift the car up. “I didn’t realize I was that strong.”Lou Ferrigno moments?Exactly.Tell me the story of your piece “Fathers of the Wild River”?I was 12-years-old and I was at this summer camp in South Carolina. There was this really awesome counselor there who was from Wisconsin. He was a real river guy. His thing was to go to the river at night. But we can’t go to the river at night, it’s a camp. You’re not allowed to leave the camp. He’s like, “we can go.” So, he got his little cabin of twelve-year olds, which is insane if you think about it, and we drove to the Chattooga River at night. We’re just hanging out there at this huge rapid called Bull Sluice at the last rapid on section three. The first rapid on section four is in Deliverance.I just kind of wandered down to the river. I’m sitting there looking at the rapid and it’s moonlit. You can feel it. It roars in your chest. I swear to God this thing told me to jump in. It said, “Jump in. You’ll be okay.” I just jumped in. It did this thing where it tosses you around. It felt like being tossed by 100 fathers. Like these guys were just tossing me around then they just released me.The expression of transitional river mythology is common, but this stems from your own experience not something you learned. You were 12. Not only was I 12, but I was a Jewish boy who had grown up in a very mundane household. I mean, my dad was a furniture salesman. My mom was like, “Don’t do that.” I was Woody Allen, basically, jumping into the river and I came out like, “these are not my people.”This was the transformative thing?Absolutely changed my life. No doubt about it. It encourages me constantly to do stupid things that I recognize that I’m going to be okay on.Like in the South Valley?Which I did not recognize to be the challenge that it currently is.Is it accurate to say that you are taking a risk with the faith that you will be okay?True, but even more so, by taking that risk that is on the edge, that it will put me in touch with a higher self. It actually will transform me because it is a risk that is consequential.

Outside In – The Mixed Media of Mitch BergOpening Saturday, May 11, 4pm to 6 pmCalliope Gallery2876 Main St.Madrid, N.M.