Bright Enough To Blind You

Last Thoughts On Luis Jimenez

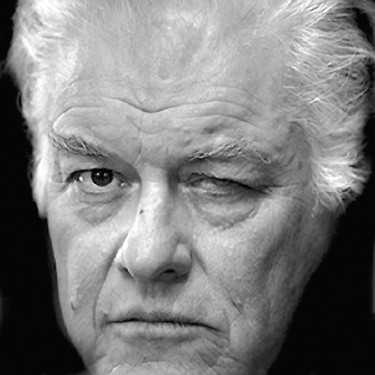

Luis Jimenez

Ricardo Barros, ricardobarros.com

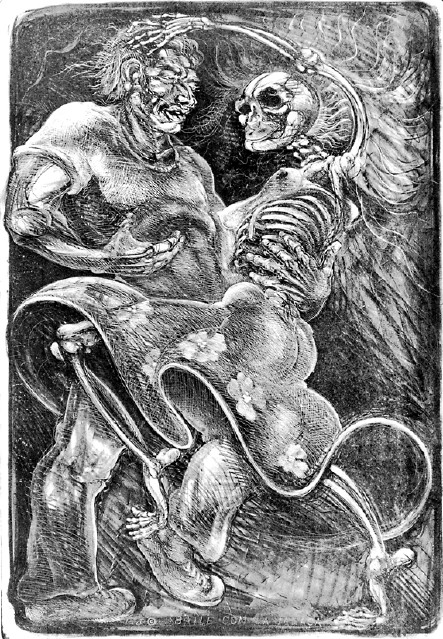

“Dance with the Skeleton” by Luis Jimenez (Albuquerque Museum collection)