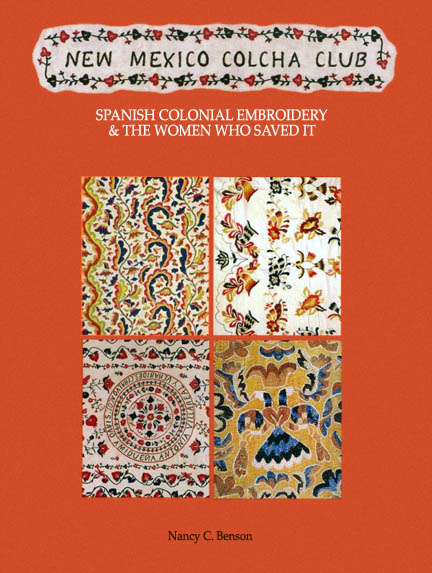

When the first settlers made their way from Spain to what is now New Mexico in the early 1600s, they brought with them the essentials: sheep, seeds and fine embroidery. Embroidered textiles in some permutation or another are a part of nearly every culture, and New Mexico’s traditional embroidery, known as colcha, sprang from the detailed work found in Europe and hauled over an ocean to New Spain.Colcha literally means “bedspread” or “quilt,” but in New Mexico it came to refer to a single stitch secured by one or more smaller stitches. Embroidery here evolved over time in such a way that it shrugged off other techniques, and its sole focus on this solitary stitch led to colcha becoming the de facto term for Spanish colonial-style embroidery. Nancy Benson’s New Mexico Colcha Club documents the history of this particular needlework over 400 years. Colcha saw its peak in the early 1800s while this region was still part of Mexico. By the late 19 th century, the tradition was nearly extinct, quashed by the influx of easily procured, mass-produced textiles from America. Colcha designs that were still created were done so perfunctorily, without the artistry of earlier generations. The craft was dying.It was in the early Depression years that then 38-year-old Teofila Ortiz Lujan, a wife and mother of four in northern New Mexico, was introduced to colcha. Lujan immediately took to it, pouring her considerable energy into becoming proficient. With a group of friends, she formed Arte Antiguo, a social club that formed the center of the revival of colcha embroidery.Other groups at this time were also looking at colcha as part of New Deal programs in the folk arts. A kind of resurgence in the craft emerged, one that continued until Lujan’s death in 1995. Upon her passing, Arte Antiguo disbanded, leaving few living practitioners of colcha. It was only then that Esther Lujan, Teofila’s daughter, understood the vast significance of what her mother had managed to do—save a unique form of artistry from extinction. Esther decided to take up her mother’s mantle and needle, making it her campaign to not only keep colcha alive, but to have it be seen as fine art.Benson’s chronicle is a vibrant history of a particular art form, and through it, an entire culture. She begins where many accounts do, with Oñate and conquered peoples, but Benson gives life to the litany of ancestors and events in New Mexico history. The narrative she crafts is loving and detailed, portraying the women who settled and built families here as brave, resourceful and self-sufficient. The book, published by the Museum of New Mexico Press, is gorgeous, and the research that went into it meticulous. This is a serious book, presented as art, and is possibly one of the best books published about New Mexico in years. It treats its subject with dignity and reverence, rendering the history of Hispanic women in New Mexico as essential, their work and artistry ignored at our own peril.

Nancy Benson will discuss New Mexico Colcha Club and show examples of colcha work on Thursday, Jan. 22, at 7 p.m. at Bookworks (4022 Rio Grande NW).