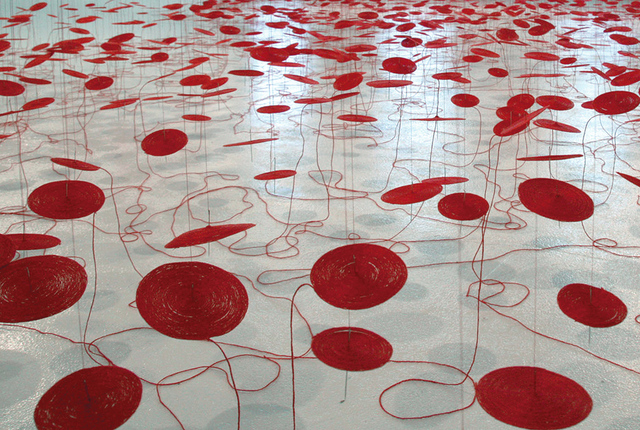

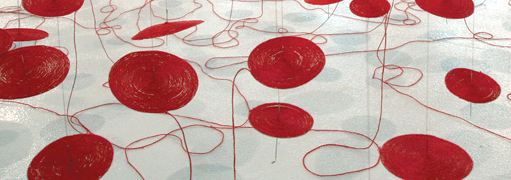

Yelizaveta Nersesova and I sit on the floor in front of her installation “A Rare Perfection of Form” for 516 ARTS’ upcoming show, Unraveling Tradition. The work is a hot-pink painted log balanced precariously on the ground. Green and yellow and blue thread encases a hook in the wood, connecting it to the wall, where the thread wraps around pins in an interwoven design. Looking at it, I’m overtaken by a sense of déjà vu.“Thread is hard to work with,” Nersesova says, “it responds to your state. It’s volatile that way.”A few minutes earlier, I’d noticed the thread vibrating in response to movement in the building. At first I’d thought of a musical instrument, but the temperamental nature she describes brings something wholly different to mind. Suddenly, I want to interact with her work—not to touch it, but to explore the three-dimensionality of it. There’s a cone within another, neither completely closed, at least not in the unfinished version. I want to stick my head inside and see what all that thread looks like as it returns to its single point on the hook. It’s reminicient of Anthony McCall’s 1973 experimental film “Line Describing a Cone,” except that McCall’s film is made of light and smoke and this is made of something tactile. McCall’s film though, which I was lucky enough to see in person once, actually seems more touchable. There’s no way to destroy “Cone,” which makes it simultaneously seem both more and less real than Nersesova’s.Because the work in Unraveling Tradition is made of fibers, materials normally touched and used, I want to lay my hands on everything. From the felt forests of Lisa Kellner’s “Almost Perfect” and “Life Support”—which remind me of another piece, Christine Margaret Wertheim’s “The Hyperbolic Crochet Coral Reef,” though made through a different technique—to the seagrass, beeswax and rawhide weaving of Sarah Hewitt’s “Beloved,” my body wants to experience them with more than just my eyes.“I love to pet them,” Hewitt says of her work. Further reinforcing my desire to explore everything in sight she says, “Almost all my pieces have some kind of smell.”I’d noticed it, too, when we passed Hewitt’s woven sculpture, but I resisted and, because it’s what I have to do, will continue to resist. Unraveling Tradition shares its opening and its venue with a sister show, filled with artists who also know just what I’m talking about. Restoration features art made by textile conservators and restorers. These are people who spend their days intimately involved with delicate fabrics and, when the workday is over, unleash their creative spirits.In her works “Three Cut Purple,” “White Velvet Flowers” and others, Ilona Pachler (who shows seven works in Restoration ) first damages fabrics by cutting and burning, then conserves them in their state of intentional destruction, while Norma Cross weaves paper, filled with images of the effects of war, the way one would normally weave fabric for “Woven Paper Number One.” Restoration curator Rufus Cohen went into the show seeking tension. “One of the inherent contradictions is that it features work by artists, but those artists are defined by their jobs” as restorers and conservators, he says. It’s an unusual focus, but one that Cohen says artists welcomed because “they’re so immersed in traditional models that they need to explore something further.”Both Unraveling and Restoration open Saturday, July 17, and share the space— Unraveling downstairs, Restoration upstairs—at 516 ARTS. During the run of the show, through Sept. 11, an installation by Unraveling artist Ellen Rothenberg expands beyond gallery walls onto D-RIDE buses. These small works utilize the buses’ advertising space and offer riders an opportunity to see art outside the art world context.These are shows that not only play with textiles but with the idea of tactility. By using materials with which the audience is familiar but placing them at a distance and in a relationship with fine art, the work of the combined 22 artists becomes alien and unfamiliar—things that are not to be handled; things that are delicate. The juxtaposition draws the viewer in further than if the works were more traditional because they tease us with a sense of the ordinary while being nothing of the kind.

Unraveling Tradition and Restoration

Runs through Sept. 11Reception: Saturday, July 17, 6 to 8 p.m. 516 ARTS516 Central SW516arts.org