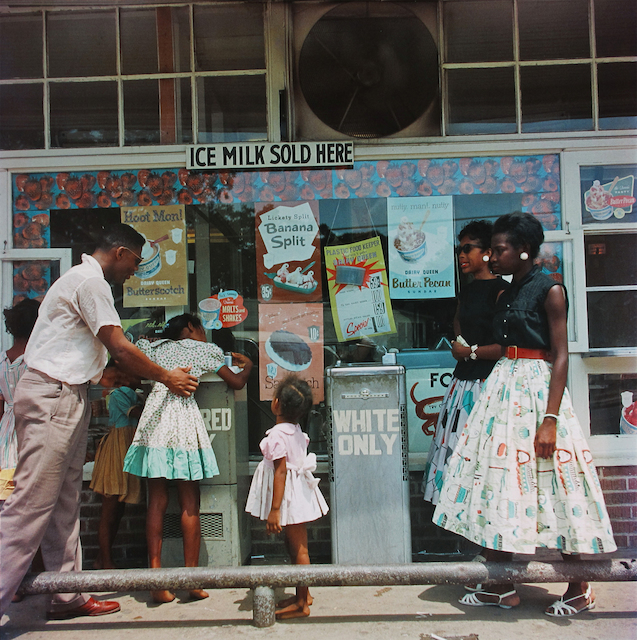

At first glance, the Gordon Parks’ Segregation Series photographs, now on display at the Richard Levy Gallery (514 Central SW), appear to have little in common with the images we traditionally associate with the fight for civil rights.There are no images of police brutality or sit-ins. The exhibit’s subject matter wouldn’t make the national news or get the Ken Burns documentary treatment. Unlike the gritty, black-and-white snapshots that haunt the pages of most of our history books, these photographs are in full color. Yet, with humility and grace, the images that appear in Parks’ Segregation Series deliver an equally powerful blow against the segregation and racism prevalent in the South in the decades before the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.Parks was on assignment in Mobile, Alabama, for a Time magazine photo essay entitled, “The Restraints: Open and Hidden,” which appeared in a September 1956 issue. Only 20 of the photographs made it to final publication, and the other transparencies were thought lost. They were forgotten until the spring of 2012, when the Gordon Parks Foundation discovered 70 dusty transparencies in the bottom of an old storage box.And what a discovery. Some of the Segregation photographs are ominous and intense, providing stark evidence of segregation’s injustice and inequality: separate entrances to department stores, “whites only” water fountains and ramshackle for-sale signs touting “lots for colored.” In one gut-wrenching image, “Outside Looking In, Mobile, Alabama,” six African-American children peer into the distance, separated behind a chain-link fence from a carnival in which a white family is enjoying the merry-go-round.Most of the images, however, focus on everyday, mundane activity. Like “Ondria Tanner and Her Grandmother Window-Shopping, Mobile, Alabama,” in which a young girl peruses a clothing store display, gazing admiringly upon the rows and rows of white mannequins in the window. Or “Mr. and Mrs. Thornton, Mobile, Alabama,” where an older couple poses plainly in their living room, with a framed photograph of their ancestors on the wall behind them and a mosaic of the younger generation’s snapshots inside the coffee table in front of them.These quiet and compelling photographs elicit a reaction that was essential to the undoing of institutionalized racial prejudice: empathy. Instead of focusing on the familiar faces and names of the civil rights movement that now highlight our history books, Parks introduced Time’s readers to the Thornton clan, who continued on with life as normally as possible during decades of Jim Crow segregation.The photographs successfully challenge racism at its very core. The ordinariness of the lives of the Thornton family shattered the delusion that somehow African-Americans are inferior to whites—a belief that pervaded popular culture at the time. For perhaps the first time, readers—both white and black—were introduced to holistic images that demonstrated the Thornton family was no different from any other American family.Just take a look at Parks’ “At Segregated Drinking Fountain, Mobile, Alabama,” the illustrative image of the collection. An African-American family takes a minute out of the hot afternoon sunshine for a cool drink of water from the “colored only” water fountain. Just as eye-catching are the females’ fashion-conscious 1950s dresses. If not for those segregated fountains, it would be the very height of normalcy. However, the reality was not all sunshine and pretty dresses. In Parks’ posthumous memoir, A Hungry Heart, the photographer dedicates an entire chapter to this very trip documenting segregation in the Deep South. Parks recalls that while scouting African-American families to photograph in Alabama, the bureau chief assigned to be his guide leaked his whereabouts to a white supremacy group. Then, upon publication of Parks’ photo essay in Time, the magazine donated $25,000 to help the Thornton family relocate after part of the family was forcibly removed from their Shady Grove, Alabama home by an angry mob.Like the history it documents, viewing the Segregation Series is equally uplifting and harrowing. It’s easy to skim over some of the less desirable pages of our history books, yet the Gordon Parks’ Segregation photographs serve as a lasting reminder of the people who lived with segregation—and persevered despite of it.

Gordon Parks, Segregation Series opening receptionSaturday, Feb. 1, 6 to 8pmRichard Levy Gallery514 Central SWlevygallery.com, 766-9888Exhibit open until March 1Gallery Hours: Tuesday through Saturday, 11am to 4pm