Lit Oblivion: The Cruel Songs Of Comte De Lautréamont’s Les Chants De Maldoror

Comte De Lautréamont’s Les Chants De Maldoror

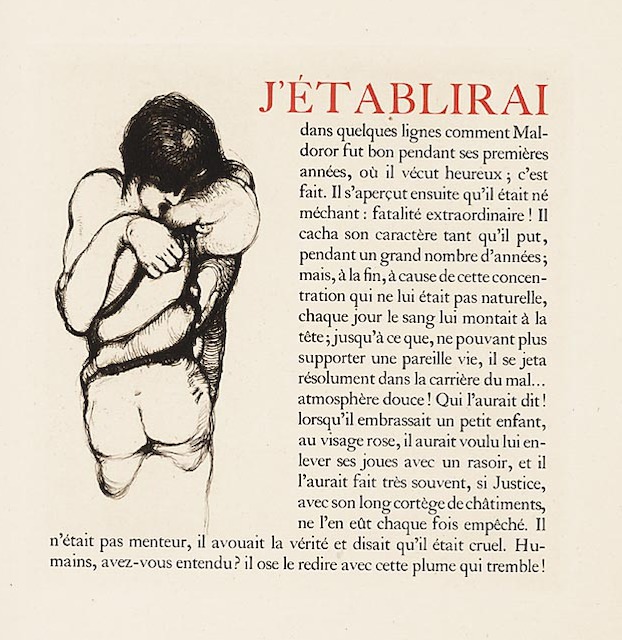

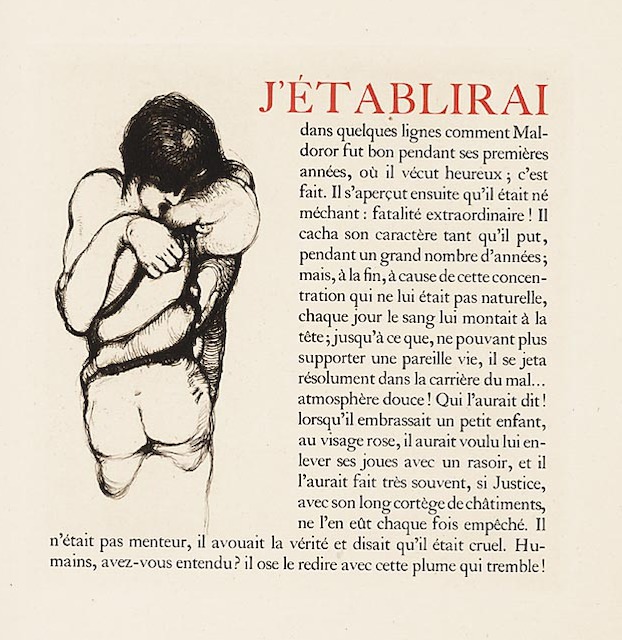

Frans De Geetere

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992

Frans De Geetere