Culture Shock: Catching Glimpses

The Wheat-Pasted Photographic Murals Of Jetsonorama

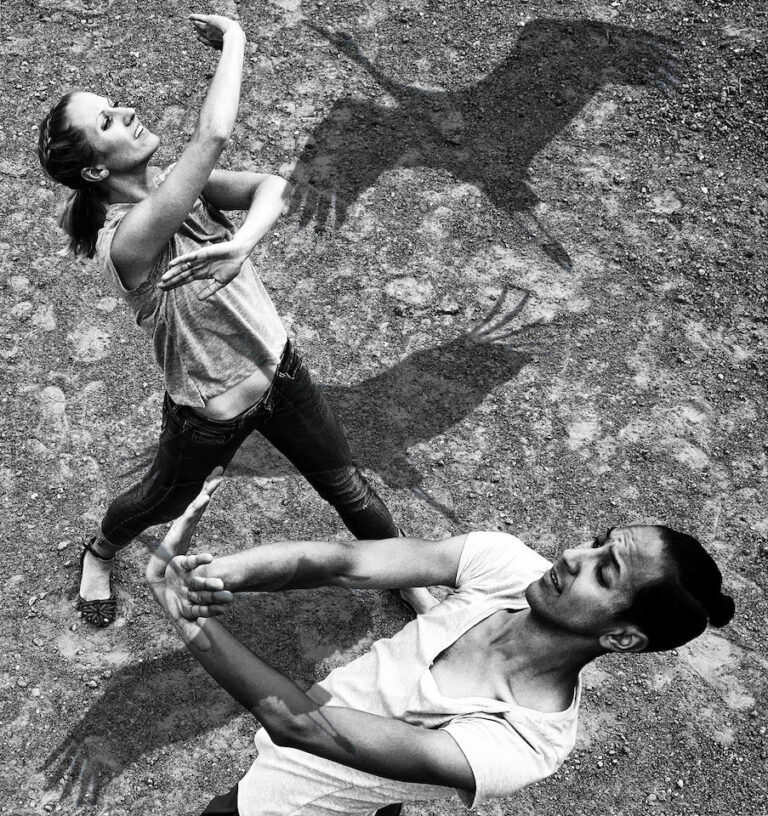

Golden Migration

Chip Thomas and Lisa Nevada

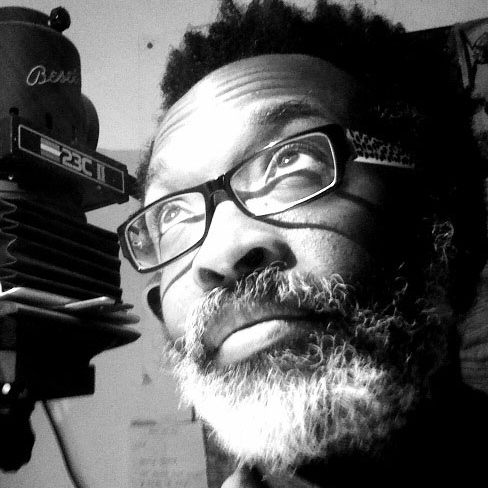

Documentary photographer and public artist Chip Thomas, also known as jetsonorama

Chip Thomas