The southern continental border of the United States stretches nearly 2,000 miles then veers right into the heart of presidential politics. What should and should not come over that border, and more specifically, what to do about it, takes up a vast amount of space in the national consciousness. Polls show a country of voters divided, but there is unity among a large block of non-voters: the animals that actually live there. It turns out, a wall isn’t so great for them.As part the regional collaboration Species in Peril Along the Rio Grande, 516 ARTS and the University of New Mexico’s Art & Ecology program are bringing together a panel of experts for a public conversation about the impact of changing conditions along the US/Mexico border. Among the panelists is borderlands historian Samuel Truett, Associate Professor of History at the University of New Mexico. Weekly Alibi sat down with Truett to talk about the history of our southern border and what borders mean for the animals that must cross them. The following is an edited version of that conversation.Weekly Alibi: How does a wall on the Southern border of the US put species in peril?Sam Truett: There are a number of species all along the borderlands that move back and forth. The present day border cuts through a number of larger ecosystems like the Chihuahuan Desert, the Sonoran Desert and the Sky Islands, which are these mountain ranges up at the top of the northern edge of the Sierra Madras coming up into the bootheel area of New Mexico, coming into southeastern Arizona where you have particular species who live at higher elevations. Because they live at higher elevations, it’s as if they’re living in islands up in the sky. That’s the name, Sky Island. From the perspective of many ecological communities, the border doesn’t really make that much sense at all. In a nuts and bolts way, a wall that won’t allow certain larger animals in particular to migrate north and south is going to have a big impact on where they get to live. Probably what most environmental activists think about when they think about animals and the wall are the big charismatic species, the jaguars and the wolves. Creatures that have a large range.That’s right. And they also have a certain sort of exotic element to them. Really from the late 19th century forward, there was a sense among American hunters, and then increasingly American biologists, that Mexico, and particularly the Sierra Madres, was a last repository for big game animals in particular that used to range a bit more widely across the North American West. A lot of the big charismatic species that people are thinking of are species that are more plentiful in Mexico and are going to be prevented from coming to the US side. On top of that, you have to add climate change which has been going on for quite a while. You’re starting to see species of all sorts beginning to move further north and beginning to move higher in elevation. The wall is just going to become a structural issue for those kinds of migrations as well. There are going to be all kinds of species that people aren’t even thinking about right now that are going to be impacted in a significant way by the wall if it’s built.Do we need a wall on the southern border at all?For most of the history of the US/Mexico border, there were no walls. Walls are a relatively recent thing. The first fences to go up along the US/Mexico border weren’t built until 1909 or 1910. The reason for the fences there wasn’t to keep humans from crossing from one side of the border to the other, but to keep tick-infested livestock from crossing to US ranches from Mexican ranches. It was Texas fever, which was infecting a lot of these animals, that brought about the first fences. Fast forward, let’s take one really iconic part of the border wall which has been there for a while, the one that goes out into the Pacific Ocean south of San Diego. If you were to visit that particular part of the border in the late-1970s, it was still a five-wire barbed wire fence. That was it. It’s not really until you get to the Secure Fence Act of 2006 that you really start to see any kind of significant wall building at all. What you would have in the past was a situation in which people weren’t really so concerned about large numbers of humans moving across the border, but they were much more interested in traditional border things like people bringing property across the border and not paying tariffs on that property, not so much the movement of people, which is the thing I think that obsesses many of us today. In some sense, the Soviets just woke up one day, realized what they were doing wasn’t working and tore down the Berlin Wall. Could we do that?History plays out for us a series of scenarios in the past that may or may not be what we’re looking at in the future, but it can help us think about how change takes place. But, historians make horrible prophets, as they like to say.Do fences make good neighbors?Sometimes.

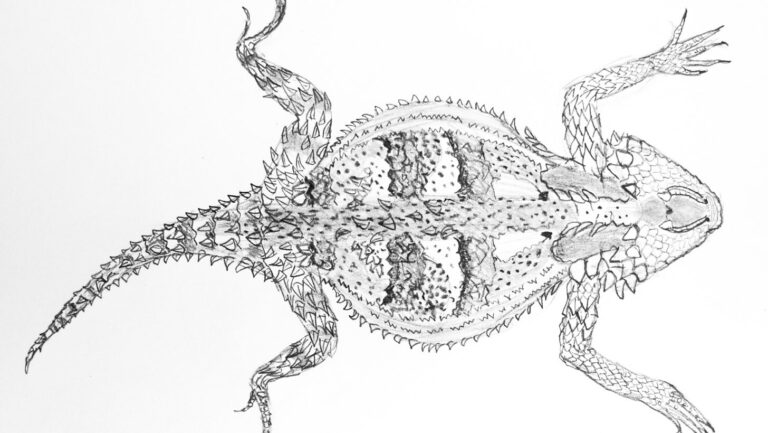

Species in Peril on the Borderlands

Poetry & Public Forum

Friday, Nov. 15, 6pm

516 ARTS

516 Central Ave. SW