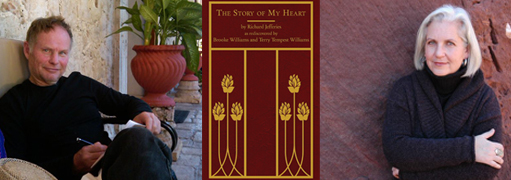

“There is a poverty of the soul we are currently experiencing.” It was a gloomy Southwest day, a rare grayness encasing Albuquerque, and Terry Tempest Williams was talking to me via phone about the publishing endeavor she’s undertaken with her husband Brooke Williams. The result of it is a slim, beatific book on humans in nature called The Story of My Heart , originally published in 1883 by Richard Jefferies, an English nature writer, now fleshed out with the responses of these modern-day counterparts.It’s easy to neglect Jefferies’ name in favor of Terry Tempest Williams’. After all, she’s a famed naturalist, activist and writer of numerous acclaimed books. But for Terry and Brooke, who’s also an eminent conservationist and author, ignoring Jefferies’ words would be a grave mistake. They first galvanized Terry in a dusty bookstore a few years ago while traveling with Brooke in Maine. “I loved the title,” she said. “My eyes have no fidelity; they are very promiscuous and it absolutely captivated me.” She was reading and paging through the old, used copy of The Story of My Heart she had unearthed when Brooke found her and glanced through the book himself. His own response was tinged with anger: “I was frustrated that I hadn’t heard his voice before,” he said. As two prominent environmentalists, the Williamses are no strangers to the world of nature writing; “this was the kind of stuff we read constantly,” Brooke said. Yet neither had heard of Jefferies before, and they doubted that more than a handful of others had, “eco-conscious” or not. Jefferies is an unfamiliar name in the modern environmental movement not because he didn’t write adeptly or prolifically (19 books published in his lifetime), but perhaps because of the many voices he used. In addition to The Story of My Heart , he wrote nature essays, children’s books, and among his novels is one of the first post-apocalyptic accounts of England. After buying Jefferies’ autobiography-cum-manifesto, the Williamses went to a beach and read from the secondhand book to each other. They found Jefferies’ words both electric and overwrought, his flowery Victorian-era writing style and transcendental euphoria ringing with “echoes of Whitman, Emerson, Thoreau and Dickinson, an attentiveness to the natural world—the wisdom was coming up through the pages.” In the book Jefferies walks through the countryside surrounding his England farm with a naturalist’s knowledge and a poet’s powers of description. “I am under no delusion,” he writes, “I grasp death firmly in conception as I can grasp this bleached bone … that the soul is a product at best of organic composition; that it goes out like a flame.” Jefferies, ultimately, is obsessed with the human soul, how it fits together with the natural world. He believes in a “soul-life” that can develop through being awake in the simultaneous abundance and cruelty of nature. “We are in a very narcissistic age,” Terry said. “We ask—what can the wilderness do for me? Jefferies was not about a solipsistic relationship to nature.” Indeed, the 19th-century “mystic” views nature as “distinctly anti-human.” For Jefferies, inscrutable nature can disrobe a human mind of civilization’s mantle. But, he reasons, one does not have to outfit herself with mountaineering gear and disappear for months to decipher nature’s mystery. “Just by being out wandering, a place where the natural system is intact, truths are available,” said Brooke. The couple converses with Jefferies in the book as if with a new friend. Terry introduces the text with the story of her relationship to Jefferies. Her honest and striking voice describes how she and Brooke followed Jefferies to England and back, visiting his family farm and imagining him walking the bluffs. Brooke, for his part, engaged in an even deeper conversation with the British nature writer. “My obsession,” Brooke said, “was two things: What is at the root of Jefferies’ words? And why now?” He answers these questions with astuteness and great depth of feeling. His own anecdotes become ecstatic, revelatory, as they succeed each of Jefferies’ 12 chapters. A story of violently hitting a golden eagle with his car becomes, through the lens of Jefferies, a vital lesson in the study of a soul. The Williamses’ writings help break up and elucidate the sometimes-woolly pastures Jefferies walks. What becomes clear is that through a regular practice of walking, of being in the natural world, the universe is open, alive. In contemporary society, this is a crucial antidote to the machinations of our lives. “We privilege the mind, the economy, capitalism,” said Terry. “Right now, especially with Ferguson, the grand jury’s decision in New York, climate change, we need to open up to a deeper sense of humanity and compassion.” Brooke and Terry believe deeply in the ability of The Story of My Heart to provoke outings into the strange and spectacular world. Jefferies’ prescient call for solitude in nature has proven itself worth fresh consideration.

Terry Tempest Williams and Brooke Williams in Conversation: The Story of My Hear t Saturday, Dec. 13, 7pm Albuquerque Academy Simms Center for the Performing Arts6400 Wyoming NEbkwrks.com, 344-8139 FREE , registration required at bit.ly/1vFSiMq