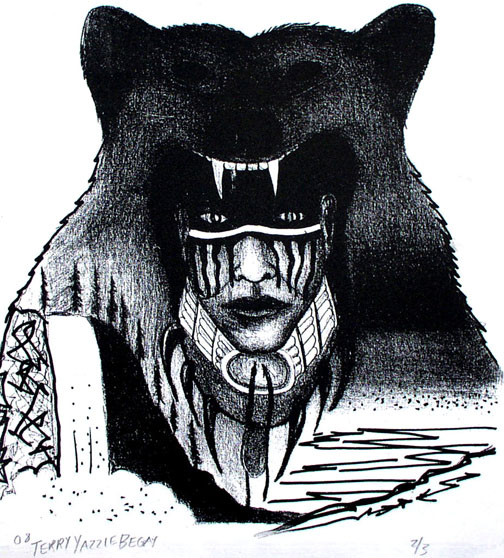

Community is a word that gets thrown around a lot in the art world—how art brings community together, how community fashions dialogue, etc. It gets so much play that its meaning can be lost or rendered redundant. But the thing is, ArtStreet is really, really about community. ArtStreet is a project from Albuquerque Health Care for the Homeless. It strives to foster a creativity-centered cooperation for those with and without homes, and it’s been recognized for its work in the form of a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. That’s the big time. Aside from funding, an NEA grant says your project—in this case, working with homeless and at-risk people to make art—is vital to our national character.ArtStreet Program Coordinator Mindy Grossberg says the NEA grant’s purpose is to “increase artist excellence through writing and art.” ArtStreet developed a program in two parts to address this mission, with a written component headed by poet Manuel Gonzalez and visual instruction with artists Leo Neufeld and Augustine Romero. Over the course of the two six-week programs, the lead artists held workshops with ArtStreet clients, working with them to develop art that challenged each person to stretch beyond their perceived limitations.Just as the very concept of the project prioritizes collaboration between visiting artists and ArtStreet artists, there was a symbiosis between the different pieces of art that each participant developed. Grossberg says the idea was to have ArtStreet participants look at their own visual work and pull out words. They also created visual art from their written pieces, making connections between the different methods of meaning. In one segment, Gonzalez provided the topic “Where I Come From,” and ArtStreet artists, as well as teachers, wrote poems. Artist/Instructor Leo Neufeld then helped them create art from that work. The results are stirring. Some chronicle the hard path of abuse that led them to the streets, while others focus on the clarity that producing art has brought to their lives. The relationships are sometimes unexpected: Autobiographical poems are accompanied by surreal landscapes, and portraits are created from image-laden verses.ArtStreet’s show Synergy: Word + Visual Art + Printmaking finds a home for the month of March in the North Gallery of the Harwood Art Center. Harwood Executive Director Stephanie Gabriel sees the partnership with ArtStreet as perfectly natural, as Harwood’s mission is to allow “access to arts for everyone.” The upstairs galleries at the old elementary school are usually dedicated to community programs, high schools and emerging artists. “Where else do homeless artists get to have a professional show?” Gabriel asks.The gallery space itself is dominated by text that wraps around the room. The words are an Exquisite Corpse, a poem that’s created by a group of people. (One person writes a line then passes it to the next writer, who continues it and so on around the group.) On the east end, a large 3-D installation hunkers next to the wall. Rising two feet off the ground, it’s a miniature recreation of a highway, one that loops around through a desert covered in dirt and pinto beans mimicking rocks. Billboards designed by participants dominate the landscape. The signs came out of an exercise directed by Augustine Romero that used the phrases “Horizon Line” and “Front View” as starting points to create images. The roadside signs were in turn inspired by the those images, which now hang above the roadway. The billboards, as in real life, are cultural messages that, according to Romero, represent what “they’re forced to deal with in their daily lives.”In addition to the work being shown this month at the Harwood, Synergy will move to the Tamarind Institute in April, where workshoppers will showcase their prints. Tamarind staffer Shelly Smith concedes that working in lithography was "challenging" for participants, as it’s a rigorous, precise process. But both the individual and collaborative pieces that came out of it not only reflect the valuable experience ArtStreet’s artists have gained but also highlight what Smith calls the Tamarind Institute’s "big mission to educate the community about lithography and fine art printing." The experience has been transformative for everyone. Artist/Instructor Neufeld is a classically trained portraitist, not a writer. But the structure of the program required everyone to try everything. In writing about where he came from, Neufeld addressed his parents’ experience as Holocaust survivors. This included an expletive-heavy passage that he had to read aloud. The experience was raw but telling. All involved were cutting loose from limitations, and the ArtStreet artists produced work that Neufeld calls “totally unexpected” and different than what they had done before. Terry Begay is one of those artists. He’s been going to ArtStreet’s open studio for four years, for up to 10 hours a week. (“Whenever they’re open, I guess,” he says.) He had made art before venturing into ArtStreet but had never really concentrated on it. “ArtStreet made me take it seriously. I realized talents I didn’t know I had.” On the Tuesday before the show’s opening, Begay is helping to hang the show. While he moves with slightly less assuredness than the professional artists around him, he’s careful with each piece, holding it as if it were precious. For Begay, the most important thing he’s gotten out of his experience with ArtStreet is “self-discovery. By doing what I really like to do,” he says, looking at what he’s just hung, “because it really comes from the heart.”